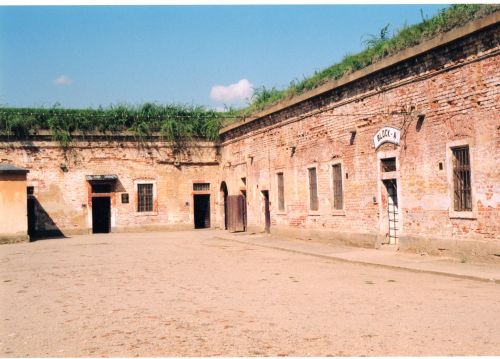

German Barracks Theresienstadt 1940

The foundation of the town of Terezin dates back to the late 18th century when Emperor Josef II drawing on his experience from several Prussian – Austrian wars decided to build a fortress at the confluence of the Labe and Ohre Rivers. The fortress –town was named after his mother Maria Theresa. Its mission was to prevent any future penetration of enemy forces into the Bohemian interior along the Dresden – Lovosice – Prague route, as well as guard the Labe waterway. The stronghold built over the period of ten years, consisted of the Main and Small Fortress, alongside a fortified area between the New and Old Ohre Rivers. The fortifications consisted of a number of elements – massive bastions, ravelins, lunettes, bulwarks, flood-moats and an extensive network of underground passages. The basins occupying two-thirds of the surrounding belt of the fortress could also be flooded. The stronghold however, was never tested in battle and its fortifications, practically impregnable at the time of construction, gradually grew obsolete. Finally the fortress was vacated and Terezin turned into a garrison town. It took little time in the 19th century for the penitentiary within the small prison to gain a notorious reputation. It functioned well into the 20th Century. During World War One the Small Fortress functioned as the Habsburg Monarchy prison, and amongst its inmates were the plotters of the Sarajevo assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and Gavrilo Princip who carried out the attack. He died in the Small Fortress in 1918.

After the German occupation in 1938 Terezin was renamed Theresienstadt. The Small Fortress became a police prison of the Prague Gestapo in June 1940 – mostly political prisoners were detained there. The creation of a ghetto, in the town itself – the former Main Fortress was an ideal location for the Nazi plans and Reinhard Heydrich took immediate advantage of it when he became Deputy Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. On 10 October 1941 he summoned Eichmann, Mauer and other SS personalities to meet him and his assistant Governor Karl Hermann Frank in Prague. Heydrich had already picked out Theresienstadt among other fortified and enclosed sites. He used expressions like Zentralstelle und Sammellager to describe it, but he made it quite clear that the inmates already depleted by hunger and overwork would eventually be evacuated. On 24 November 1941 a ghetto was established in the eighteenth –century fortress, built for the Emperor Josef II in 1780 -84. The first Jewish construction workers arrived from Prague and Brno, to be followed by family transports. At the end of 1941 there were already 7365 Czech Jews in Theresienstadt. They lived in close confinement in the former Austrian barrack blocks and had no contact with the 7,000 civilian inhabitants, who did not leave until June 1942.

On 20 January 1942 Heydrich announced at the Wannsee conference that Theresienstadt was under consideration as a special ghetto for Jews over 65 years of age and Jews with serious wounds or high decorations from the First World War. This was a change of policy for hitherto Jews of these categories had gone to Poland or Russia, as Hitler declared earlier “that the swine got their decorations fraudulently in any case.” But if Theresienstadt remained throughout the war the privileged ghetto of the exempted classes, it never lost its original purpose, that of a transit camp for Jews, and the Jews of Bohemia – Moravia who from the start Heydrich intended to deport to the East. With the departure of the Czech inhabitants in June 1942 the first of the privileged Jews from Germany and Austria, mainly war veterans and the very old. Other categories included Jews married to Aryans, half Jews who professed the Jewish faith, senior civil servants and members of the Reichsvereinigung.Then there followed a flood of deportees, who had simply bought their exemptions. During the year 1942 Theresienstadt received 32,988 Jews from the “Old Reich”, 13,922 from Austria and 54,827 from the Protectorate. One of those sent to Theresienstadt was Richard Goldshimdt better known as Richard Glazar describes his time at Theresienstadt:

By the time I got to Prague it was already ‘Jew-free’ as they called it. We stayed at the Mustermesse two or three days and waited. They distributed food and there were sinks to wash in. We slept on the ground – of course there were a great many rumours of every kind and there was this fear of the uncertainty, but there was no physical fear. One morning they counted us and we went to the nearby station and travelled to Theresienstadt, a village around the fortress north of Prague, built in the time of Maria Theresa, which had been turned into a huge internment camp. I was assigned quarters in a stable – two cousins found me there – they were in an attic. Richard Glazar stayed in Theresienstadt for a month working in the garbage disposal unit – he found his maternal grandfather and his paternal grandmother – they had been there for several months. His grandmother lived in a room with a dozen other old women, sleeping on blankets on the floor. Richard Glazar said “she seemed very small – I used to bring her chocolate whenever, I could scrounge some, but she always said “no thank you, keep it for yourself”. But then one day I brought her a pot of lard and she accepted that. My grandfather was in an old people’s ward that was really terrible. He was almost blind – he had tried to cut his veins.” After a few days in the stable he was moved into a large hall where he met another Czech Jew Karel Unger, who was to become his closest friend. Richard Glazar recalled: After a month in Theresienstadt I was notified that I was to leave the next day for another camp in the East. I ran to see my Hannah my cousin – she said grandfather had just died – it was that day too. We our Czech transport travelled on a passenger train, leaving Theresienstadt on 8 October 1942 on transport BG 417 – destination the death camp Treblinka in Poland.

Terezin 2005 - Reception Building

No phase in the deportations from Hitler’s Greater Reich was more murderous than the first year’s clear-out of Theresienstadt. Out of 43,879 deportees only 224 survived the war. At the very moment Heydrich was telling the delegates about the privileged ghetto in January 1942 – there had already been a deportation from Theresienstadt to Riga. Between March and July 1942 there were deportations to “Lublinland”, between July and September 17,004 Jews were deported to the Minsk region. Between 19 September 1942 until 22 October 1942, 18,004 went straight to the Treblinka death camp (including Richard Glazar), and 4,000 to Belzec death camp.On 26 October 1942 the last transport of 1942 left Theresienstadt for Auschwitz – since this transport included some young men, mixed in with the elderly, 28 managed to survive the war out of 1,866.

In the autumn of 1942 a crematorium was built to burn the corpses of all those Jews who had perished in the camp, due to sickness, starvation, overwork and ill-treatment by the SS guards. Those who arrived before the summer of 1943 at Theresienstadt by train arrived at the country station of Bohusovice, walked the three kilometres to Theresienstadt. The railway which was built with ghetto labour ran now from the ghetto to the station at Bohusvice. The railway line ran in front of the Hamburg Barracks, and a transport of Jews from Holland was filmed arriving at the Hamburg Barracks.

At the instigation of the German’s a Jewish Elder was appointed. He was Jakub Edelstein and he made particular efforts to try and improve the living conditions for the teenagers and children. In November 1943 he was deported to Auschwitz where he was later shot, together with his wife and son. The work of the Jewish Council of Elders in the Magdeburg Barracks covered every branch of activity in the ghetto. The Secretariat maintained the statistical records. An economics department was in charge of labour details, nutrition, laundry and allocation of space. A financial department was responsible for the book-keeping side. A technical department supervised water and power supplies construction maintenance and the fire brigade. There was also a health and social welfare department in charge of the health centres, the youth homes, old people’s homes and burials.

At the Magdeburg Barracks there was also a hall in which theatrical performances were given such as the children’s opera Brundibar, which was performed more than fifty times. Its composer Hans Krasa, was a Jew, who was imprisoned in Theresienstadt, who later died in Auschwitz. Some months before Edelstein’s deportation he was succeeded by Dr Paul Eppstein, who was also later taken to the Small Fort and shot. Eppstein had been a young official in Berlin in 1933, working for the representation of German Jewry, under Leo Baeck, a fellow prisoner in Theresienstadt.

On 24 August 1943 1260 children from the liquidated Bialystok ghetto arrived in Theresienstadt. They were kept in strict isolation, and then sent out with fifty- three volunteer doctors, nurses and attendants from Theresienstadt. As they left on 5 October 1943 the Germans said they were going to be exchanged for German Prisoners of War in Allied hands. The exchange would take place in neutral Switzerland, some said Palestine – however, they were taken to Auschwitz and murdered. From May 1943 the Market Square was covered with a circus tent divided into three parts, and used for slave labour. In one section, the inmates of the ghetto assembled wooden crates. In another they packed equipment, which had been made nearby, designed to protect motor engines from freezing, an essential component of army vehicles on the Eastern Front. In all 1,000 prisoners worked there, the tented area was surrounded by a high fence, and closed to anyone, who did not work there.

In the early months of 1944, when for the purpose of the Red Cross visit and propaganda film, the ghetto was transformed – for the so-called ‘Improvement Action’. The tents were taken down and the square was turned into a park, with a music pavilion in front of the café at 18 Neue Gasse. Allotments were created across the moat, impressive gardening work was undertaken, and this was seen by the Red Cross delegation who visited the ghetto on 23 June 1944. The ‘Improvement Action’ ensured that everything looked just right – a band consisted of inmates played on the bandstand, children dressed in clean clothes, rode on a merry-go-round. The Ghetto Elder Dr. Paul Eppstein, was given a car and a chauffeur. The Red Cross visitors saw the chauffeur open the door, bow and let him in. The day before, this same chauffeur – an SS- man- had beaten Eppstein without compunction and resumed with this treatment after the visitors had departed. The Red Cross visitors were not shown the barracks crowded with the old, the sick and the dying – nor were they shown the storerooms filled with the belongings taken from their Jews on their arrival.

A film of Theresienstadt was made in 1944, filming commenced on 16 August and was completed on 11 September, the last commandant of Theresienstadt SS- Obersturm Karl Rahm, was ordered by his masters in Berlin, to commission a film called ‘The Fuhrer Gives the Jews a Town.’ The film does not appear to have been shown during the war, it was made under the direction of German –Jewish actor and director Kurt Gerron, who had been deported from Westerbork in Holland, after he had fled from Germany, with a documentary film crew from Berlin. Berlin decreed that only prisoners who looked like Jews could appear in the film – they had to be hook-nosed, dark hair, dark eyed and preferably furtive in manner, this created a problem Theresienstadt was filled with blond, blue-eyed Jews – the woman’s high –jump champion of Czechoslovakia, a Jew was forbidden to participate in the filming of an athletics event – she had blonde hair. The ghetto’s bank was filmed, as was the Post Office where prisoners received fake packages. On the riverbank, a swimming event was held. The national high-diving champion performed for the cameras. Just out of range were boats filled with armed SS-men, just in case any of the contestants decided to swim to freedom. For days the cameras whirred, the lights were focused on the stunned prisoners. A meeting of the Jewish Council was moved from a dingy room in the Magdeburg barracks to a bright room in the gymnasium. Dr. Eppstein addressed his colleagues, but no sound was recorded. Gerron’s film took on a life of its own – firemen in new uniforms put out a fire in the gym; “The Tales of Hoffmann” was performed. In the VIP barracks; a garden party was filmed including Rabbi Baeck, Field Marshal von Sommer, the Mayor of Lyons M. Meyer and several Czech ministers. When a train bearing Jewish children from Holland arrived Rahm himself was there to welcome them, lifting the youngsters from the wagons, all dutifully recorded. Then abruptly, the filming ended – the technicians were ordered back to Berlin, Gerron was discharged, band concerts were terminated, dancing was forbidden.

The camp slipped back into its cruel, starved routine – the old and ill died and the same children Rahm was seen welcoming were murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Several still photographs made from the film still survive today, one shows Dr Eppstein addressing his colleagues. His faced is strained, his mouth is drawn, his eyes are frowning and a perplexed vertical crease separates his eyebrows. Dr Benjamin Murmelstein his aide and successor, sits by his side, staring gloomily ahead. On Eppstein’s left breast pocket, is a cloth Jewish Star – the Nazis left a morsel of truth in the film. In the beginning of 1945 a gas chamber was built in an underground passageway, but it was not used. In the last weeks of the war thousands of young Jews who had survived the death marches and death trains were brought to Theresienstadt, some lived in the Hamburg Barracks, Moniek Goldberg a Polish Jew recalled “whilst the Hamburg Barrack was an improvement on the journey – it soon turned into a nightmare.”

In the face of the advancing Russian forces the Germans started to liquidate camps in the East and transfer the prisoners to other camps, including Theresienstadt. These newcomers were infested with lice and in April 1945 a typhus epidemic broke out which soon claimed hundreds of victims. Shortly afterwards the SS tried to assemble two transports for an unknown destination. Fearing the Nazis intended to cover up their war crimes, by staging a massacre, the Jewish Council refused to co-operate and smuggled a warning to the Red Cross in Prague. On 19 April 1945 Paul Dunant the Swiss Red Cross representative, who had visited Theresienstadt, on 6 April 1945 and had been personally escorted by Eichmann, approached Karl Hermann Frank and obtained his assurance that there would be no more deportations from Theresienstadt. Anxious to open negotiations with the Americans, Frank was now posing as a moderate, using the surviving Jews as evidence of his goodwill. Under Red Cross supervision Jews were transferred from Theresienstadt to Switzerland and Danish Jews were sent to Sweden. On 2 May 1945 the SS guards fled from Theresienstadt and two days later a group of Czech volunteers arrived to help the ghetto medical staff the typhus epidemic, which had already claimed the lives of 44 doctors and nurses. On 8 May 1945 the first units of the Soviet Army appeared and placed Terezin under strict quarantine. By June the outbreak was over and the prisoners were able to leave. Theresienstadt came under the control of Eichmann’s office in Prague, headed by Rolf Gunther, the commandants were all members of Eichmann’s staff. They were;

Siegfried Seidl – November 1941 – July 1943

Anton Burger – July 1943 – February 1944

Karl Rahm – February 1944 – May 1945

Seidl and Rahm were executed after the war, but Burger escaped and has never stood trial for his crimes. Heinrich Jockel the commandant of the Small Fortress was arrested, tried for war crimes, and executed after the war. 140, 000 Jews were deported to Theresienstadt, 75,500 from the Czech lands, 42,000 from Germany, 15,000 from Austria, 5000 from Holland, and the rest from Hungary, Denmark and Poland. Today the Small Fortress and Ghetto can be visited as well as the Crematorium site and National Cemetery

Sources

G. Reitlinger, The Final Solution,Sphere Books London 1953

Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust, Collins London 1986

G. Sereny, Into that Darkness, Pimlico London 1974

Sir Martin Gilbert, Holocaust Journey, Weidenfeld & Nicolson London 1997

C. MacDonald, & J. Kaplan, Prague – In the Shadow of the Swastika, Quartet Books Ltd

Terezin – Places of Suffering and Braveness – published for the Terezin Memorial Praha 2003

Terezin Memorial Museum

Harry Stadler

Photographs – Chris Webb Archive

Terezin Gallery

Terezin - Fortress Walls 2005

Terezin Block A - 2005

Terezin - Arbeit Macht Frei Gate 2005

Terezin - Commandants House 2005

Terezin - Kommandantur 2005

Terezin -Cemetery in front of Small Fortress 2005

Terezin - Small Fortress 2005

Terezin - Reception Shower Room 2005

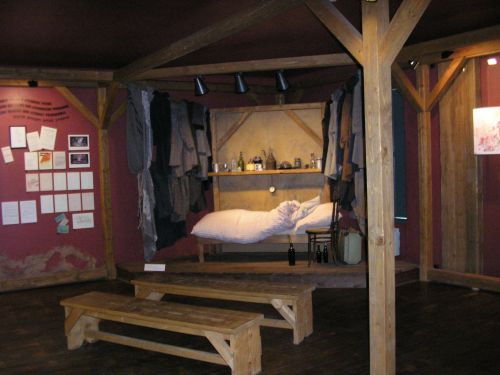

Terezin - Inside one of the barracks 2005

Terezin Ghetto - Judenrat Building

Terezin Ghetto - General View 2005

Terezin - Magdeburg Barracks (Yellow Building -Red Roof) 2005

Terezin - Crematorium 2005

Terezin Bohusovice - Railroad Tracks and Crematoria 2005

All photographs - Chris Webb

Thanks to Michal Chocolaty

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018