Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Eichmann (Facing the camera, on the right) SS Raid on Jewish Gemindhaus – Vienna in March 1938

Adolf Eichmann was born in Solingen on 19 March 1906. He was born into a solid middle-

In September 1934 he found an opening in Himmler’s Security Service, -

From August 1938 he was in charge of the ‘Office for Jewish Emigration’ in Vienna set up by the SS, as the sole Nazi agency authorised to issue exit permits for Jews from Austria; later this office was established in Prague, to cater for the Czech Jews and in Berlin, for the Jews in the Reich. Eichmann acquired expertise in ‘forced emigration’ – in less than eighteen months – approximately 150,000 Jews left Austria – and extortion was to prove an ideal training-

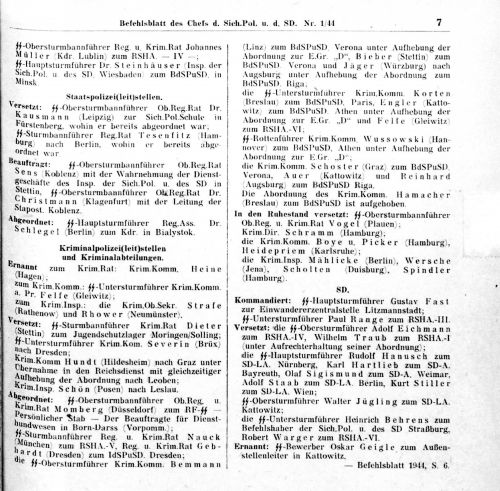

SS Befehlsblatt -March 1944 --Bundesarchiv

For the next six years Eichmann’s office was the headquarters for the implementation of the ‘Final Solution’, though it was not until the summer of 1941 that his ‘resettlement’ department began the task of organising the system of convoys that were to transport European Jewry to their deaths. It was in August 1941 that Eichmann first visited Auschwitz concentration camp, to discuss with Commandant Höss the establishment of a gas chamber by converting a peasant farmstead in the northwest corner of Birkenau. In November 1941 Eichmann was promoted to the rank of SS – Obersturmbannnführer (Lieutenant – Colonel) and he was involved in organizing the mass deportation of Jews from Germany and Bohemia, in accordance with Hilter’s order to make the Reich free of Jews as quickly as possible. Adolf Eichmann attended the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on 20 January 1942, which consolidated his position as the ‘Jewish Specialist’ of the RSHA and Reinhard Heydrich, the head of RSHA, now formally entrusted him with implementing the ‘Final Solution’. In this task Eichmann proved to be a model of bureaucratic industriousness and icy determination even though he had never been a fanatical anti-

When even Heinrich Himmler became more moderate towards the end of the war, Eichmann ignored his ‘no gassing’ order, as long as he was covered by Heinrich Mueller his immediate superior and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who had succeeded Heydrich as the head of RSHA.Only in Budapest after March 1944 did the desk –murderer become a public personality, working in the open and playing a leading role in the deportation and eventual massacre of Hungarian Jewry. He even issued a proposal to Joel Brand to deliver a message in person to the Allies, exchanging Hungarian Jews for heavy lorries. Whilst Joel Brand left Vienna for Istanbul on 19 May 1944, he was eventually arrested on the Turkish – Syrian border and then held prisoner in a villa near Cairo. The Allies refused the proposal. Hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz – Birkenau.

Though arrested at the end of the war, Adolf Eichmann name was not yet widely known and he was able to escape from an American internment camp in 1946 and flee to Argentina. He was eventually tracked down by Israeli secret agents on 2 May 1960, living under the assumed name of Ricardo Klement in a suburb of Buenos Aries.Nine days later he was abducted in secret to Israel to be tried in public in Jerusalem. The trial which aroused enormous international interest and its share of controversy took place between 2 April and 14 August 1961. On 2 December 1961 Eichmann was sentenced to death for crimes against the Jewish people and crimes against humanity. On 31 May 1962 he was executed in Ramleh prison.

Sources

R.S. Wistrich, Who’s Who in Nazi Germany, published by Routledge, London and New York 1995

Danuta Czech, Auschwitz Chronicle, published by Henry Holt and Company, New York 1989.

G. Reitlinger, The Final Solution, published by Sphere Books Ltd, London 1971

Photograph – Bundesarchiv

Document - Bundesarchiv

© Holocaust Historical Society - February 4, 2021