Jules Schelvis - Arrival in Sobibor

Sobibor 1943 - Johann Niemann photograph album (USHMM)

Jules Schelvis was deported from Westerbork in Holland to the death camp Sobibor, in Poland on June 1, 1943. The harrowing journey lasted seventy-two hours. Along with his wife Rachel, and other housemates, they had been captured during one of the big raids in central Amsterdam, and found themselves in a cattle wagon with sixty-five other people crammed inside. Those deported included babies, elderly and sick people. They were given nothing to eat or drink and had to relieve themselves in a little wooden barrel in a corner of the wagon. Shortly before they arrived the bewildered people were intimidated by the guards escorting the transport and forced to hand over their valuables. After pulling into the siding next to the camp, ten wagons were shunted inside the camp. Jules Schelvis continued the account:

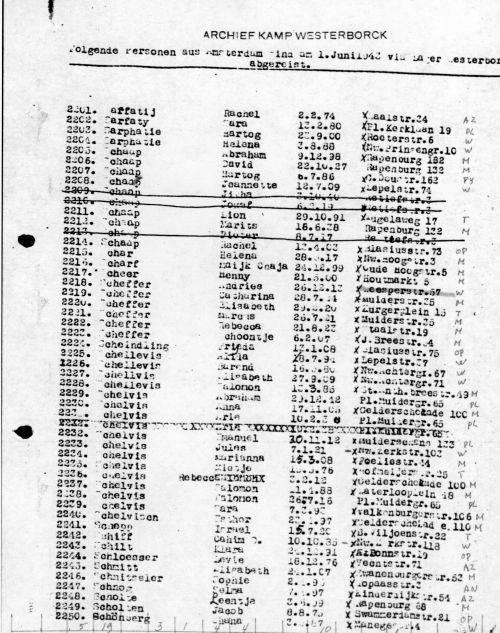

Westerbork Transport List Extract (Westerbork Camp Archive)

The Jews of the Bahnhofskommando were very heavy-handed getting us of the train onto the platform. They let on they were Jewish by speaking Yiddish, the language of the Eastern European Jews. The SS men standing behind them were shouting 'schneller, schneller' (faster, faster) and lashed out at people once they were lined up on the platform. Yet the first impression of the camp itself aroused no suspicion, because the barracks looked rather like little Tyrolean cottages, with their curtains and geraniums on the window sills.

But this was no time to dawdle. We made our way outside as quickly as possible. Rachel and I, and the rest of our family, fortunately had no difficulty in swiftly making our way onto the platform, which had been built up of sand and earth. Behind us we could hear the agonised cries of those who could not get up quickly enough, as their legs had stiffened as a result of sitting in an awkward position for too long, severely affecting their circulation. But no one cared. One of the first things that occurred to me was how lucky we were to be all together and that the secret of our destination would now finally be revealed. The events so far did not hold out much promise though, and we understood this was only the beginning.

It was obvious we had arrived at our final destination : a place to work, as they had told us in Holland. A place where the many who had gone before us should now also be working. Our presence must be of quite some importance, why else would the Germans have bothered to bring us all the way here, traveling for three days and nights, covering a distance of two thousand kilometres?

Yet the Germans were using whips, lashing out at us and driving us on from behind. My father -in-law, walking beside me, was struck for no reason. He shrank back in pain only for a moment , not wanting anyone to see. Rachel and I firmly gripped each other's hand, desperate not to get separated in this hellish situation. We were driven along a path lined with barbed wire towards some large barracks and dared not look round to see what was happening behind us.

We wondered what had happened to the baby in our wagon , and to the people unable to walk; and what about the sick and the handicapped ? But we were given no time to dwell on these things and, besides, we were too preoccupied with ourselves. 'What shall I do with my gold watch?' Rachel said. 'They will take it from me in a minute.' I replied, 'Bury it, because it could be worth a lot of money later.' As she was walking, she noticed a little hole in the sand and quickly threw the watch down, using her foot to cover it up. 'Remember,' she said, 'where I've buried it. We can try digging it up later when we have a little more time.'

Like cattle, we were herded through a shed that had doors on either side, both wide open. We were ordered to throw down all our luggage and keep moving. Our bread and backpacks, with our name, date of birth and the word 'Holland' written on them, ended up on top of the huge piles, as did my guitar, which I had naively brought and carefully guarded all the way. Quickly glancing around, I saw how it ended up underneath more luggage. It dawned on me then that there was worse to come. Robbed of everything we had once spent so much care and time in acquiring, we left the shed through the door opposite.

I was so taken aback and distracted by having had all our possessions taken from us, that although I had seen an SS man at some point, I never noticed, until it was too late, that the women had been sent in a different direction. Suddenly Rachel was no longer walking beside me. It happened so quickly that I had not been able to kiss her or call out to her. Trying to look around to see if I could spot her somewhere, an SS man snapped at me to look straight ahead and keep my 'Maul (gob) shut.'

Along with the men around me, I was driven on at a slightly slower pace to a point just past an opening in a fence, where yet another SS man was posted. He looked the younger men up and down fleetingly, seeming to have no interest in the older ones. With a quick nudge of his whip, he motioned some of them to line-up separately by the edge of the field. Directly in front of me, my brother -in-law Ab was directed to join this growing group. My father-in-law, David, and Herman, my thirteen -year old brother-in-law, were completely ignored. My father-in-law was too old, Herman too young. Glancing at me for just a moment, he let me pass as well. He needed to select only eighty healthy-looking men.

Those who had not been selected had to move along into the field and sit down. That Friday 4 June 1943, the Sobibor sun beat down on our heads. It was midday and very hot already. There we were, defenceless, powerless, exhausted, at the mercy of the Germans, and completely isolated from the rest of the world. No one could help us out here. The SS held us captive and were free to do as they pleased.

The rows of men out on the field were getting bigger as those from the other wagons joined us. While we were waiting, I had a little time to collect my thoughts. Our harsh treatment seemed to be in conflict with the image of the Tyrolean cottage-like barracks with their bright little curtains and geraniums on the windowsills. They had had such a friendly and calming effect on me after all the tensions of the preceding days. The camp had seemed devoid of any other people, apart from the Germans and the Jews who had 'welcomed' us on the platform.

As I sat there, I noticed a few Dutch prisoners had approached from the other side of the barbed wire fence and were trying to make contact with us. I recognised Moos van Kleef, the owner of the fish shop on the corner of the Weesperstraat. My arms gestured a question: how are things here, what can we expect? To assuage us, he yelled out to us that it was all right here, no reason to be concerned. I heard him say: 'We have a job here, everything is new or has to be built.' My mind was ticking over faster. I thought: this must be the new camp for which they will require some sort of order service (police). That must be why they need those young men. My intuition told me I would want to be a part of that group. Not so much for the order service, but to be with my brother-in-law whom I could still see in the distance.

The field had become quite crowded and I had already come to terms with the idea of working in the camp when I saw the same SS man approaching. With his hands behind his back he ambled past the rows of men quite smugly, seeming quite pleased with himself. As he came closer, I suddenly remembered the order service. He had almost passed when I jumped up and put up my hand. I asked permission to ask him a question. Glancing back at me quite affably, he hesitated briefly and then nodded his approval. I requested in my best German, to join the other group. He stared into the distance, tapping his whip against his boot a few times. He turned around and asked: 'How old are you?' I replied: 'Twenty-two, Herr Officer.' Healthy? 'Jawohl, Herr Officer.' I had no idea what his rank was. 'Can you speak German?' Jawohl, Herr Officer.'

Not altogether disinterested, he searched me with his eyes for a moment, apparently lost in thought. Then nodding his head in the direction of the group, he said: 'Na Los.' I quickly ran towards it. The young men, relieved at finally being able to release some of the tension built up over the past few days, were chatting to an almost amiable SS man there. To my joy, my best friend Leo de Vries was also among them. The German looked surprised when I joined them, because he believed the eighty-strong group to be complete. A little incredulously he asked: 'They sent you as well? So now we have eighty-one; one too many, because to my knowledge there should only be eighty.'

After standing around and exchanging thoughts for a while, we were cut off abruptly by the SS man, who, suddenly in quite a different tone of voice, told us to shut up. He continued: 'My colleague has selected you to work at another camp not far from here. You will return to Sobibor every evening so you can meet and enjoy yourselves with your family and friends.' Pointing towards the field , he carried on: 'They are going to have a bath now. This is why the men have been separated from the women, because they obviously cannot bathe together. All the others who arrived today will stay here.

As he spoke, I also saw the SS man addressing the men out on the field, though I could not hear his exact words . Obviously they were being told to undress, because I saw them starting to take off their clothes. By the time 'our' SS man had lined us up in rows of five, all those out on the field had already removed their shoes and vests. Urged on by his loud Eins-Zwei-drei-vier cadence, he tried to get us to march smartly and in step towards the camp exit. He could not imagine how miserable we were after being scrunched up for days inside the cattle wagons. On our way to the train I must have passed the spot where Rachel had buried her watch. I could not remember it. But I thought I might remember again in a few hours' time, when, on my return, I would be headed in the same direction as when we arrived.

Two wagons and an engine stood ready for departure. All traces of turmoil had been erased from the platform, as though it had never happened. The train arrived in Trawniki on the very same day, 4 June 1943. The group had to walk the remaining five kilometres from there to Dorohucza. Unlike other people, I never did see the narrow gauge railway at Sobibor, and neither did I see any people being thrown into rail carts. A possible explanation could lie in the fact that we were the first to enter the camp, so the sick and elderly would not have made their way onto the platform by then, and the tipper trucks were not yet required. They must have been there, ready for use, but without people screaming inside them I probably did not notice.

Jules Schelvis pictured in Westerbork

Jules Schelvis was born on January 7, 1921, in Amsterdam. He worked as a typographer and he was arrested with his wife Rachel, who was 20-years of age on May 26, 1943, and sent to the Westerbork Transit Camp, with other members of Rachel's family.

They were all transported to the Sobibor death camp from Westerbork on June 1, 1943, and they arrived there on June 4, 1943, where the majority were murdered, apart from Jules who was selected for work, and sent by train onto the Dorohucza Labour camp , via Trawniki. At Dorohucza, Jules worked cutting peat in very harsh conditions.

Jules Schelvis and others volunteered for work in a print-shop at the Alter-Flugplatz - Old Airfield in Lublin, but there was no print-shop just heavy labour. After a short time on June 28, 1943, he was transferred to the Radom ghetto along with other Dutch Jews, this time to work in a genuine print-shop. When, the Radom ghetto was finally liquidated on November 8, 1943, he was moved to the nearby Szkolna camp.

With the advance of the Red Army, Jules Schelvis was forced to walk to Tomaszow Mazowiecki, where they were locked in a rayon factory. From there he was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he was selected on the ramp for forced labour in another camp. He was sent to work in a Labour Camp in Vaihingen, near Stuttgart. He was liberated by the Allies on April 8, 1945.

After the war he was an expert witness at the trials of Karl Frenzel and John Demanjuk and he was the author of several memoirs and historical studies about the Sobibor Death Camp. Jules Schelvis passed away on April 3, 2016, in Amstelveen, Holland.

Sources

Jules Schelvis, Sobibor, Berg, Oxford, New York, 2007

Chris Webb, The Sobibor Death Camp, Ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart, 2017

Document: Westerbork Camp Archive

Photographs: USHMM and Private Archive

Thanks: Aline Pennewaard, Wally Delang

© Holocaust Historical Society, December 17, 2020