Ghettos

Overview

Radom Ghetto Sign

Ghettos were not a Nazi invention; their origins can be traced back to medieval times, when restrictions on the places where Jews were allowed to reside were commonplace throughout Europe. The term ghetto was Italian in origin and Venice created a ghetto in the 16th century in a part of the city that had been an iron foundry, but ghetto’s had been established in cities such as Prague, Frankfurt am Main and Mainz in the 13th century.

In 1791, Catherine the Great created the ‘Pale of Settlement’ in western Russia. Most Jews were only allowed to reside within the ‘Pale,’ and even there some cities were prohibited to them. Even earlier in 1290, Edward I had expelled all Jews from England. They were not officially permitted to return until the time of Oliver Cromwell in 1655.

To an extent, only being allowed to live in specified parts of a city presented no great problem to an almost wholly Orthodox community. Judaism with its many religious requirements encouraged Jews to live in close proximity to each other and their religious institutions. Whilst they were generally free to come and go within the cities and towns in which they dwelt, until the mid-19th century, there were special Jewish districts called ‘Jewish Towns’ in many larger Polish cities and towns.

This was particularly true of places that until the end of the 18th century were the property of the Polish Kings; Jews could only live in these specified districts. They were not permitted to live inside the towns ‘walls’ in the so-called ‘Christian towns,’ although Jews were permitted to trade with Christians and to even rent small shops within the Christian sector. In towns belonging to the Church, Jews were not allowed to settle at all until 1861-62. By way of contrast, in smaller provincial towns which were the private property of aristocratic families, Jews were welcomed because of the economic benefits they brought. It was frequently a less than idyllic existence, but it was bearable. Anti-Semitism was endemic, based upon religious bigotry and economic envy. From time to time the anti-Semitism erupted in pogroms, most notoriously under the leadership of Bogdan Chmielniecki, who between 1648 –1656 is estimated to have murdered half-a-million Jews in Poland and parts of the Ukraine – a loss of Jewish life only to be exceeded by the Holocaust.

The assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881 unleashed a wave of anti-Jewish violence that resulted in the start of mass emigration from Russia and Poland to the west, a process that continued largely uninterrupted until the outbreak of the First World War. An even bloodier series of pogroms during 1903 -1906 only served to increase the flood of European Jews seeking shelter from persecution. Having relocated to new countries, Jews tended to congregate in particular areas of cities and towns, even when no longer forced to do so. That was a matter of personal choice, strength in numbers, seems quite a sensible and logical approach.

When the Germans invaded and then occupied Poland this led to ghettos being re-established again in the 20th century. Reinhard Heydrich, Head of the Reich Main Security Office, and the leading organisational architect of the ‘Final Solution’ instructed the senior Einsatzgruppen commanders in Poland on 21 September 1939, stated that:

For the time being, the first prerequisite for the final aim is the concentration of Jews from the countryside into the largest cities. The Jews must be grouped together, there must be no Jewish communities of less than 500 souls, and these only where a railway passed.’

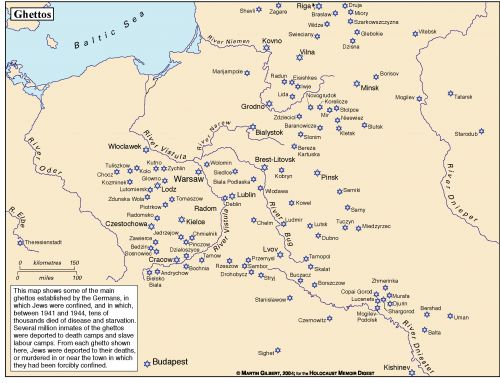

The establishment of ghettos were seen as a temporary measure, until the ‘Final Solution’ of the Jewish question was implemented. The Jews were also ordered to form a Jewish Council (Judenrat) to administer the ghettos, usually these men were experienced in serving their communities. The first decree creating a ghetto was issued in Piotrkow Trybunalski as early as 8 October 1939. Another early ghetto was established in Pulawy in the Lublin district at the end of November 1939. The first permanent ghetto was established in Tuliszkow, Turek county, in December 1939 or January 1940. Thereafter ghettos/ Jewish Living Areas were introduced over periods of time- Litzmannstadt (Lodz) in April 1940, Warsaw October 1940, Krakow March 1941, Lublin April 1941, and after the invasion of the Soviet Union, Lvov in December 1941.

Ghettos in Europe 1941 -1944 (Sir Martin Gilbert)

The creation of the ghettos / Jewish Living Areas proved to be an enormous challenge. The Jewish population was uprooted, the non-Jewish residents moved from the area selected. Some ghettos, particularly in the larger cities and towns were sealed by walls, barbed wire fences and armed guards, whilst others in smaller communities were open and left unguarded. What was common, in the larger cities and towns the areas chosen for the ghetto was inevitably situated in the most impoverished parts of the cities and towns. The housing was dilapidated, often with no piped water or electricity. The number of people packed into the ghetto / Jewish Living Area, produced staggering levels of population density, for example in Warsaw, 30% of the population was forced to live in only 2.4% of the city’s area.

Warsaw and Litzmannstadt (Lodz) were the two largest ghettos, together housing nearly one-third of all Polish Jews under the control of the Nazis. Because of their size, the lack of food was a major problem. As a consequence malnutrition and disease stalked the ghettos. Rations were imposed by the German authorities at a level impossible to sustain life. The quality of the food was often poor or inedible, and only widespread smuggling made survival possible.

Despite the immensely harsh conditions in the ghettos, Jewish religious and cultural life continued to flourish. There are accounts of musical, operatic and theatrical performances and many examples of poetry and artwork have survived to provide eloquent testimony of the Jewish spirit. Libraries were maintained and although education was forbidden, children secretly attended schools and adults continued to study religious texts. Jewish festivals and religious holidays were covertly observed, marriages celebrated and ritual circumcision performed on newly born male children.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable aspects of life in the ghettos was the determination of the Jews to record their experiences. In Warsaw, on the initiative of Dr. Joseph Milejkowski, a group of doctors began research into the clinical aspects of starvation, from which they themselves were also suffering. In many ghettos, a communal chronicle or diary was maintained. Some of these were lost, some survived and are considered the most important accounts of life in the ghettos. Of particular note, the Warsaw ‘Oneg Shabbat Archive’ of Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum and the diaries of Adam Czerniakow, the Warsaw Judenrat Chairman and Chaim Kaplan. Chronicles of the Lodz and Kovno ghettos have also survived.

The life span of the ghetto’s varied from place to place; some existed for only a few months, whilst others lasted a few years. On 19 July 1942, Heinrich Himmler ordered Friedrich – Wilhem Krüger, Higher SS and Police Leader in Nazi – occupied Poland, and Odilo Globocnik, SS and Police Chief of the Lublin District and the head of Aktion Reinhardt to eliminate the residual Jews in the Generalgouvernement by 31 December 1942. No Jews were left to remain unless they were in the ghettos of Warsaw, Krakow, Czestochowa, Radom and Lublin.

In the case of Litzmannstadt (Lodz), it was the first major ghetto to be established in April 1940, and it was the last major ghetto to be liquidated in August 1944, with the ghetto inhabitants being sent to Auschwitz,- Birkenau concentration camp, due to its contribution to the German war effort. Why Litzmannstadt ghetto survived so much longer was down to the efforts of Chaim Rumkowski, the Judenrat Chairman, and its key role in supplying the German forces with material, produced in its factories and workshops.

Sources:

Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990.

R. Hilberg, The Destruction of European Jews, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2003

Y.Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw 1939-43, The Harvester Press, Brighton 1982

J. Bacon, The Illustrated Atlas of Jewish Civilisation, Quantam Books Ltd, London 1998.

R.S. Wistrich, Anti-Semitism – The Longest Hatred, Thames Mandarin, London, 1992

G. Reitlinger, The Final Solution, Vallentine Mitchell, London 1953

Photograph: Yad Vashem

Map: Sir Martin Gilbert

© Holocaust Historical Society March 31, 2021