Budzyn Labour Camp

SS-

Budzyn is located about 4 miles to the northwest of Krasnik. In the mid-

The Budzyn forced labour camp, which was initially subordinated to SS-

From the summer of 1942, various groups of Jews were transferred to the Budzyn camp, including 100 Jewish women from the Belzyce ghetto and about 500 Jews from the remnant of the Krasnik ghetto. Other groups arrived subsequently from the camps in Goscieradow, Hrubieszow and Krychow. The Jews living compound was comprised of six barracks, similar to those in the Lublin concentration camp, constructed by the first prisoners, plus a kitchen barrack and a toilet barrack. It was surrounded by a barbed-

On 1 May 1943, 807 survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, who had first been sent to the Lublin concentration camp, were selected by the then commandant SS-

By the summer of 1943, Air Ministry priorities had changed, and production of parts for the Heinkel HE 219 in the Heinkel-

News of the massacres soon spread via the Ukrainian guards, demoralizing the spirits of the prisoners, which had been raised by news of the Soviets forces advances. Following rumors of possible liquidation, a group of prisoners tried to escape a few weeks later. The Ukrainian guards not only shot those trying to escape; they also dragged more than 30 other prisoners from their barracks and murdered them inside the compound. The women were housed in a separate barracks, which the men were not permitted to visit. However, men and women were able to meet and talk for a few minutes every day outside the barracks, and some love affairs flourished. By January 1944, the food rations were so poor that prisoners without access to extra rations wasted away. Those unfit to work were sent to the camp hospital, where they quickly died.

The Budzyn camp was relocated at the end of January 1944 to another newly constructed camp about 2 miles away, known as ‘Barrackenbau’ now much closer to the Heinkel factory. Here the prisoners also received striped uniforms and a prisoner number. The transfer took several days. At the new location, the camp was somewhat larger and surrounded by an electrified fence. Several hundred sick and weak prisoners, including many women, were not transferred but shot on the spot. This relocation reflected the ‘official’ integration of the camp into the concentration camp system, and SS-

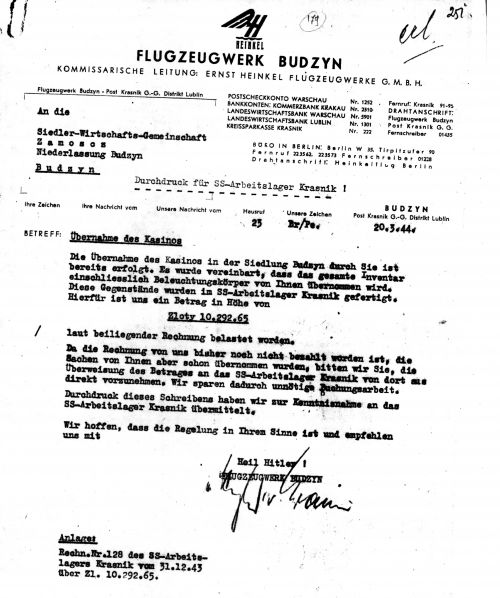

Budzyn Correspondence - Chris Webb Private Archive

Prisoners recall that the daily rations slightly improved at the new camp, consisting now of a piece of bread with margarine and soup with even a couple of potatoes in it. Punishment in the form of beatings was administered in front of all the prisoners on the parade ground. Some useful prisoners received special privileges, including Morris Wyszogrod, who painted artworks for the commandant, and Jakob Eljowicz, who was the SS portrait photographer. When there was an escape in February 1944, Wyszogrod was ordered to draw a plan of the camp, marking the point of escape to accompany the official report. Despite the camp’s formal designation as a concentration camp, certain cultural privileges were granted by the camp’s leadership. Just prior to the move in January 1944, the prisoners put on a humorous show, involving songs and skits. Then at Passover in 1944, thanks to the influence of Jewish camp elder Noah Stockman, unleavened bread was baked, and a Seder ceremony was held.

After the last director of the Heinkel –Budzyn factory conceded in January 1944, that much of his workforce was not being used to their full capacity, the Armaments Inspectorate withdrew its resistance to the workforce being deployed elsewhere. As a result, the Heinkel labour force declined by some 50 percent in February 1944. Throughout the spring and early summer of 1944, there were various selections in the camp, as weaker prisoners were designated for death and groups of workers were sent to other camps. Among the destinations of prisoners from Budzyn in this period were the Heinkel factories in Mielec and Wieliczka and also the Lublin concentration camp.

The camp was finally evacuated in July 1944, in the face of the advancing Soviet Red Army with many of the prisoners being taken initially to Wieliczka and subsequently toward Germany. The proportion of survivors from the camp was relatively high, compared with other Jewish labour camps in the area. Josef Leipold, who was born on 10 November 1913, in Altrohlau, the camp commandant following its relocation in January 1944, was extradited to Poland by the Americans in 1947. He was tried by the district court in Lublin and sentenced to death on 9 November 1948. He was executed by shooting on 8 March 1949.

SOURCES:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-

J. Marszalek, Majdanek – The Concentration Camp in Lublin, Interpress, Warsaw, 1986

Photograph: Yad Vashem

Document: Chris Webb Private Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2020