Chelm

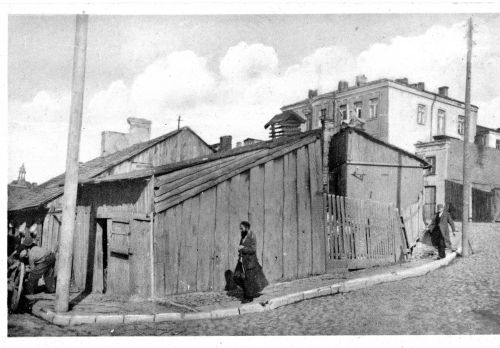

Chelm -Poststrase (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Chelm lies 43 miles east-southeast of Lublin and approximately 16 miles west of the River Bug, the border with Ukraine. In August 1939 the population stood at 33,622 people, including some 15,000 Jews. Most were artisans or merchants, mainly in livestock, tanning and trading in hides. The Jewish community had three savings –and-loan associations, print shops, traditional Jewish charitable and welfare societies, and a chapter of TOZ (Society for the Protection of the Health of the Jewish Population in Poland). In Chelm there were Jewish schools such as traditional Hadarim that also taught Hebrew and Polish, primary schools that taught in Yiddish, a Hebrew-language Tarbut school, Yeshivot, a religious school for girls, a Hebrew language high school which closed in 1935, and a Polish-language high school. Various Zionist parties, Agudath Israel, and the Bund operated in Chelm. A few Jewish members of the clandestine Polish Communist Party lived in the town. There was a Jewish sports club, a library and three Yiddish newspapers.

The Second World War saw a Luftwaffe bombardment on 8 September 1939 which claimed about 200 lives, including at least 30 Jews. On 25 September 1939 in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Red Army occupied Chelm. After a subsequent border demarcation on 28 September 1939, the River Bug was designated as the German – Soviet frontier and hundreds of Jews joined the Red Army’s evacuation on 7 October and two days later on 9 October 1939, the Germans occupied Chelm. On 25 October 1939, the SS newly stationed in Chelm took some 20 wealthy Jews hostage, demanding 100,000 zloty for their release. Once freed, the ‘hostages’ served as the intermediaries between the authorities and the Jewish community. The SS selected from among the hostages, almost all members of the Jewish Council (Judenrat), including its chairman, industrialist Majer Frenkiel. The Jewish council organised a 150-strong Jewish Order Service, to maintain law and order. In December 1939, a ten –member Judenrat under the merchant Frenkiel was established, other Judenrat members were Biederman, Dreszer, Tenenboim and Frajberger, were recalled by Gitl Libholer, after the war. On 30 November 1939, SS- Obersturmbannfuhrer Hager, the newly appointed Stadtkommissar of Chelm, demanded the Jewish Council the next day assemble 2,000 adult Jewish males on Plac Luczkowski for an inspection by a visiting delegation, including Hans Frank, head of the Generalgouvernement and SS- Gruppen Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, Higher SS and Police Leader East. At the square, members of the 5th squadron of the 1st SS- Reiterstandarte surrounded the assembled Jews and ordered them to march to Hrubieszow, which was some 30 miles away. The SS shot half the marchers dead during the journey there. German reports note 440 of 1,018 Jews were shot for attempting to escape. In Hrubieszow, the police the next day added more than a 1,000 men to the survivors ranks, divided the column in half and then compelled the men to cross the German-Soviet frontier near Belzec and Sokal. Hundreds perished near Sokal, when the Soviet border guards initially refused the men passage. Wartime Jewish sources noted 400 Jews returned to their homes in Chelm, whilst 1,600 lost their lives on this brutal forced march. On 30 October 1940, Miller, the newly appointed Stadtkommissar, effectively established a ghetto in south-central Chelm by banning Jewish residence in northern and central neighborhoods. Miller’s order prohibited Jews from residing on 17 streets, including Narutowicz, Bwowarna, Nadrzecza, Jordanska, Piromowicz, Ogrodowa, Strzacka, Reformacka, and Kopernik. Jews living on the named streets had until 10 November to report to what Miller called the ghetto. On 27 November 1940, Miller ordered the Jews to evacuate Lublin Street. A March 1941 article in the Gazeta Zydowska (Jewish Gazette) noted the Jewish Council had averted the German authorities plan to fence the ghetto in. Miller’s orders left for the ghetto a small sliver of the old Jewish neighborhood, from which Christians were never evicted.

In April 1941, 11,000 Jews, including 400 refugees, resided there. That month, Frenkiel reported: ‘The Jewish population in Chelm is confined residentially to an extremely narrow area in which space is limited. Several dozen reside in a single room.’ By December the Jewish population had increased to 12,500. The Germans permitted Jewish craftsmen, businessmen, and health professionals to establish small private enterprises in the ghetto. In June 1941, some 1,400 craftsmen, which was100 fewer than before the war, held artisan licenses. They established 300 workshops, mainly tailoring, shoemaking, and carpentry enterprises. Another 540 Jewish-owned enterprises, mostly stores, employed 1,736 Jewish workers. Non-Jews entered the ghetto to order services from the craftsmen. They used specially marked front doors on the business establishments. Jews entered through the back doors. Inadequate rations required most to leave the ghetto to find food and heating fuel. Death was the penalty for leaving the ghetto’s boundaries without permission and for transactions in food officially denied Jews. Though severe beatings were more common, several Jews found outside the ghetto were executed. The victims included three women discovered purchasing milk on a market day. Questions nonetheless remain about whether a ghetto existed in Chelm, mainly because in September 1941, Hans Augustin, the newly appointed Kreishauptmann of Chelm maintained that no ghettos existed anywhere in his Kreis. The fact that Augustin was responding to a Reich Interior Ministry inquiry about available space for incoming Jewish deportees undoubtedly shaped his response. Augustin explained he was contemplating a ghetto for Chelm but had postponed its establishment, as no room existed there for additional Jews. On 31 May 1941, 1,800 Jews from Chelm worked for several large German concerns on road and railway construction projects, in forestry labour, at a quarry, at a sawmill in Zawadowka village, and for the military. Another 250 were interned at labour camps, the majority at a camp established by the Inspectorate of Water Regulation (Wasserwirtscharfsinspektion) in Kamien. In June 1941, 100 additional ghetto residents became the first inmates of another Water Inspectorate camp, established in Chelm to reclaim swampland. Another 1,200 Jews from Chelm performed forced labour each day. Women worked as domestic servants for German civilian and military authorities. Men worked on public works projects, unloading coal at the railway station, removing gravestones from the Jewish cemetery to use as paving for pavements and extending the municipal water system. In the spring of 1942, when the German authorities moved Stalag 319 from Okszowska Street, conscripts dismantled the old prisoner-of –war camp and buried hundreds, if not thousands, of dead Soviet soldiers in the nearby forest. The Jewish Council permitted wealthier Jews to purchase exemptions from forced labour obligations. The council, in turn, offered volunteers, the poorer Jews 3 zloty for a day of substitute labour. To establish a welfare system for the impoverished the Jewish Council and the Jewish Social Self-Help (JSS) branch, also led by Frenkiel, used profits from a jam factory, and when the German authorities closed it in mid-1940, they imposed an income tax on ghetto residents. By late 1941, three community kitchens, a medical clinic, and a 25-bed hospital for infectious diseases, established in November during a typhus epidemic, cared for 6,828 impoverished prisoners. The child welfare programmes established by JSS activist Chaja- Roza Oks, the wife of a physician murdered in the December 1939 forced march, to care for the neediest of the ghetto’s 5,000 children were considered the most developed of their kind within the Lublin District. By May 1941, they included a public school for 700 impoverished pupils, aged 7 to 12, free medical care, free meals daily for another 600 children, and a summer camp to provide special nutritional care to 110 of the most impoverished. At the summer camp they served two meals daily and the campers gained 2 kilograms on average. A ‘Drop of Milk’ initiative provided pre and post-natal care to 450 infants and their mothers. Volunteers organized games at a playground to provide 500 needy children a daily opportunity for play. German rationing policies undermined the welfare programmes, threatened the Jews physical existence, and – when beneficent – increasingly accelerated the authorities’ direct interference in the private lives of Jews. In March 1942, the Kreishauptmann’s office for example, extended to Jews for 12 groszy, a bar of soap and enough detergent to launder one outfit. It was the first time Jews in Chelm had received these items. However, the German authorities tied their distribution to a Kreis-wide ‘Cleanliness Week’ advertised under the slogan, ‘We are destroying lice!’

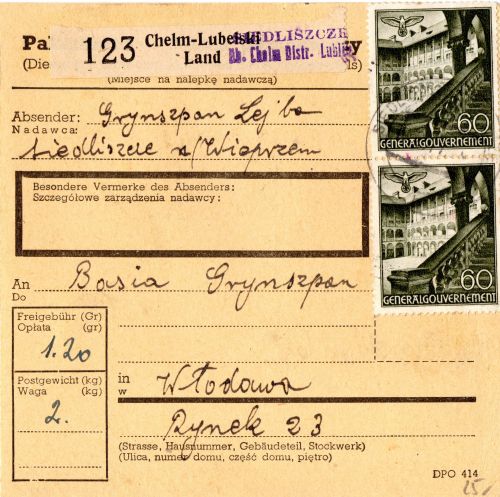

Chelm - Wlodawa - Paketkarte

From 22 March until 27 March 1942, Jewish authorities and German officials supervised Jews throughout the Kreis, as they cleaned their persons, belongings and homes and removed items from the attics, basements and storage facilities. Abram Cytron noted that this last order made it more difficult to hide during the expulsions. In April 1942, during the initial phases of Aktion Reinhardt in Chelm, the SS according to survivor Gitl Libholer, began marching through Chelm Jewish deportees from nearby communities as distant in the north as Sawin and in the south as Wojslawice. The 20 April deportation from Wojslawice included 209 Jews – the deportees were all over 60 years old. On 10 April or 11 April a group of the deportees were sent to their deaths at the Belzec death camp. Because later deportees sent to Wlodawa, never arrived there, they are presumed to have perished at Sobibor death camp. In late April 1942, the SS ordered the Chelm Judenrat to prepare a list of 3,000 elderly Jews for ‘immediate resettlement.’ On 11 May and 12 May 1942, 2,000 Slovak Jews from Humenne and Zilna arrived in Chelm. The SS confiscated the deportees baggage, making them dependant on the Judenrat. On 18 May 1942, the SS marched through Chelm non-working Jews from Siedliszcze, a Jewish community, which in January 1942 had numbered 2,026. Because the 1,000 to 3,000 Slovak deportees sent to Siedliszcze in April for work at the Water Regulation Authorities camp, almost all, were camp inmates, they formed an insignificant part of the deportees destined for Sobibor death camp. The retention of labour camp inmates and working Jews motivated Frenkiel to attempt to blunt the forthcoming ‘Aktions.’ He offered to recruit immediately for Holzheimer, the Wasserwirtschaftsinspekteur for Kreis Cholm, 7,000 men and women from the ghetto for the organisation’s eight labour camps. When the Cholm Landkommissar offered to shield from deportation volunteers for agricultural labour on his estate in Ruda-Opalin, it became a refuge for the native elderly. The Judenrat protected others considered vulnerable, including 600 orphans it began placing in early May with foster families and probably also sending some to Ruda. Frenkiel’s protection of native Jews, and the fact that many of the Slovak deportees were older, sealed their fate. On 22 -23 May 1942, the Shavuot holiday eve, some 4,300 Jews were sent by rail to Sobibor death camp including 1,000 elderly Jews from Chelm. The deportation was much larger, as it included small-scale expulsions from nearby eastern communities. In Dubienka, for example, a part of the town’s 2,700 Jews were expelled on 22 May 1942. Gitl Libholer recalled that Dubienka Jews were among the deportees who passed through Chelm in the spring of 1942. In Chelm, a raid of forced labour sites at the end of June 1942 trapped about 1,000 underage or elderly public works conscripts and Water Regulation camp inmates deemed unfit for work. Holzheimer may have intervened to reduce to 300 the number sent to Sobibor death camp. In a larger ‘Aktion’ in mid-August, remembered as the so-called ‘Kinder Aktion’ the SS sent to Sobibor between 3,000-4,000 Jews, including most of the ghetto’s children, the unemployed and the remaining elderly. The ghetto area was reduced in size to establish what the German authorities had planned in June 1942, as a ‘compact quarter.’ It was composed of Szkolna, Uscilugska, Pocztowa, Siedlce and Katowska Streets. Jews living outside its borders were required to report to the ghetto in late August. The ghetto was unfenced. The Jewish and Polish (Blue) Police patrolled its internal and external borders, watching over the 5,000 Jews who lived there.

On 25 October 1942, SS from Lublin and Ukrainian SS volunteers from Trawniki ordered all ghetto residents to assemble on the Siedlce Street square. In a two-day ‘Aktion’ some 2,000 Jews were marched via Wlodawa to the Sobibor death camp. Many Jews evaded deportation by hiding in the ghetto, or with local Christians. Between the 5 November 1942 and 9 November 1942, the ghetto was liquidated. Late on 5 November the SS began transferring 500-1,000 workers, craftsmen, Jewish Council members and their families outside the ghetto to labour camps and to vacant public buildings and barracks. The next morning, after surrounding the ghetto, SS and Ukrainian troops ordered its inhabitants to assemble on the square. The deportees were marched to the railway station and the first batch went immediately to Sobibor death camp. Others were held in a fenced holding facility established at Kolejowa Street and they were sent to Sobibor in the days that followed. While searching for people hidden in bunkers, the SS set fire to many of the ghetto buildings. Some Jews uncovered during the searches were marched first to the holding facility and then onto Sobibor, whilst others were killed on the spot. By 13 November 1942, the SS announced all Jews could enter a camp established on Katowska Street, at the pre-war Staszic public school for 370 workers held back from the deportations. Several hundred fugitives who reported there were executed. Jews retained for labour resided mainly at the pre-war Staszic School or at the railway station barracks, known as the craftsmen’s camp. When typhus engulfed both camps a few weeks after the liquidation of the ghetto, the SS executed in the Borek woods, hundreds of sick inmates. The Jewish Council members, initially held at the Water Regulation camp, also were shot. In January 1943, the prisoners at Staszic School, including members of the Jewish police, were deported to their deaths at Sobibor. In the spring, after the SS transferred to Sobibor the craftsmen in construction trades, 28 Jews, mainly tailors, shoemakers, and their families, were left in Chelm. However, on 31 March 1943, the Gestapo executed 20 of the Jews, thus leaving only 8 Jewish craftsmen in the Chelm prison. A number of fugitives escaped from Chelm or jumped from the deportation trains. Some with false identity papers made their way to other localities to attempt to survive as Poles. A few were sheltered by local Christians. Many more entered the transit ghetto in Rejowiec. In addition to the 8 craftsmen at the Chelm prison and at least 3 participants of the Sobibor revolt, which took place on 14October 1943, another approximately 50 ghetto residents survived the war.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

The Yad Vashem Encylopiedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust Volume 1, Yad Vashem, 2009

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

M.Gilbert, The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy, published by Collins London 1986

Statement by Gitl Libholer – 25 August 1950 – Jewishgen

Photograph – Chris Webb Private Archive

Document - Tall Trees Archive

© Holocaust Historical Society 2019