Westerbork Transit Camp

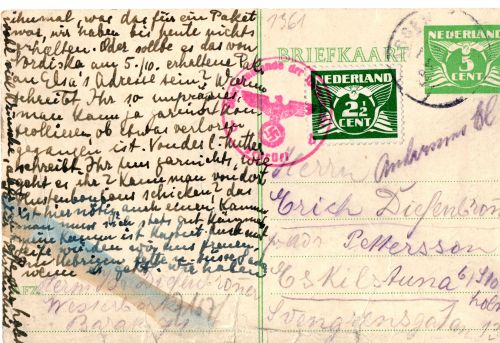

Westerbork- Postcard from Herm Isr. Diefenbroner, Barack 71 to Eskilstuna b/ Stockholm (Chris Webb Private Archive)

The community of Westerbork is situated in the northeast of the Netherlands in the province of Drenthe, 11 kilometres from Assen, the province capital, some 130 kilometres north of Amsterdam. In a resolution proposed by the Minister of Home Affairs and approved by the Dutch cabinet on February 13, 1939, it was decided to construct a camp 'to house refugees from Germany that live in this country.' The camp was opened on October 9, 1939, and the cost amounted to 1.25 million guilden, was charged to the Jewish Refugee Committee in the Netherlands.

When the Germans invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, there were 750 refugees residing in the camp. They were moved to Leewarden, capital of the province of Frisia, but they were returned to Westerbork, following the Dutch surrender. The camp came under the control of the Ministry of Justice on July 16, 1940. Refugees from other camps were subsequently moved to Westerbork, which by 1941, had a population of 1,100 in two-hundred small wooden houses. In the words of one commentator, 'it was a site about as inhospitable as could be, far from the civilized world in the isolation of the Drenthe moorland, difficult to reach, with unpaved roads where even the slightest shower would turn the sand to mud.' The camp was also plagued by hosts of flies during the summer months.

At the end of 1941, the German authorities decided that Westerbork would become a transit camp for Jews destined to be deported to the east. The camp dimensions measured 500 x 500 metres and the camp was surrounded by a barbed -wire fence and seven watchtowers and twenty-four large wooden barracks were constructed. Eventually, there were to be one hundred and seven barracks, each designed to hold three hundred people were built. The costs of this building work and for the camp's maintenance were to be financed from the proceeds of confiscated Jewish property, an amount that was to exceed ten million guilders for 1942/43. During the first six months of 1942, four hundred foreign Jews, mainly German and those deemed stateless, were transferred to Westerbork from the towns and villages in the Netherlands.

On July 1, 1942, the Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD took control of the camp and SS troops arrived to reinforce the Dutch military police guards. One of Westerbork's inmates Philip Mechanicus stated that the majority of the Dutch military police were benevolent and mild in their treatment of the Jewish inmates. Indeed this attitude may have been the reason why they were replaced from June 1, 1944, by a company of the special Police Battalion from Amsterdam, who were trained at the Nazi Police academy in Schalkhaar. Erich Deppner, a member of the German administration in the Netherlands was appointed camp commandant. He was succeeded in turn by an SS Officer Josef Hugo Dischner on September 1, 1942. Both men proved to be equally incompetent and very soon SS-Obersturmfuhrer Albert Gemmeker was appointed camp commandant on October 12, 1942. Gemmeker left the day to day operation of the camp in the hands of German Jews, as had been the case from its inception.

Albert Gemmeker, far right celebrate Christmas at Westerbork with Ferdinand aus der Fuenten who directed Eichmann's branch office in Amsterdam.

On July 13, 1942, most of the people who had lived in the camp, many of them for as long as two years, were dismissed from the camp administration. Those dismissed included everybody who was not deemed purely Jewish by the criteria established by the Nazis. One day later all inmates born between 1902, and 1925, were examined on behalf of the Arbeitseinsatz (Work Allocation Department). Deppner explained, 'Your labour is also needed for our victory.'

The transfer of Jews from Amsterdam to Westerbork began on the night of July 14/15, 1942, and the first transport left for Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp on the following day. To facilitate the transports east, on July 15, 1942, the Dutch railroad company Nederlandse Spoorwegen received an order for the construction of a 5 kilometre railroad into Westerbork camp. The timetable for the trains, their size and destination were determined by Adolf Eichmann's IVB4 office. Gemmeker left the composition of the transports to the Jewish camp leaders - the so-called 'Kampleiding'. It must be pointed out that certain inmates, such as those of foreign nationality or veteran servicemen were exempt from transportation.

The 'Kampleiding' consisted solely of German Jews, who had been in Westerbork from the very beginning and who were known as the 'Alte Kamp -Insassen (Old Camp Inmates). From Gemmeker's point of view they were easier to communicate with than the Dutch Jews. The official language in Westerbork was German. Sometimes severe tensions occurred between the Dutch and the German Jews, as the former considered the latter to be rude in their behaviour, and some of the German Jews collaborated with the SS.

Those Jews who had been caught in hiding within Holland were labelled 'Convict Jews' and were placed in a punishment block, Barrack 67, in the north-eastern corner of the camp. Unlike other inmates, they were not allowed to keep their own clothes, but were forced to wear blue overalls and wooden clogs. Men and women in the punishment block had their hair shaved off, received no soap, less food than the other prisoners and were forced to work in the most arduous labour details. The 'Convict Jews' - the Strafgevallen were in general the first to be selected for transportation on the next train to Poland, leaving on the subsequent Tuesday.

Unlike other transit camps, Westerbork maintained a relatively small semi-permanent population who remained in the camp for a considerable time, ran their own affairs and maintained a near-normal life, especially during the periods when there were no deportations. Elie Cohen, a doctor by profession, was in Westerbork for eight months before being sent to Auschwitz. Whilst never pleasant, conditions in the camp were far more bearable compared with the transit camps of eastern Europe; although the water supply was bad and washing and sanitary facilities were inadequate.

Often the camp was very crowded, ' like the last piece of driftwood to which too many drowning people try to hang on after the sinking of the ship,' as described in the famous diary of Etty Hillesum. Esther 'Etty' Hillesum was deported from Westerbork on September 7, 1943, to Auschwitz. Etty died in Auschwitz on November 30, 1943. But the great majority of those who passed through Westerbork only stayed for a few hours or days, or perhaps weeks before boarding a train destined for the east. Meanwhile the ''Kampleiding'. attempted to save people from deportation by providing them with jobs within the camp. For example, prisoners were enrolled in the Ordedienst (Jewish Police), or in the 'Fliegende Kolonne' (Flying Brigade), a section who were responsible for ensuring the transfer of deportees to the railway station in the nearby village of Hooghalen, which was used before the railroad into the camp became operational.

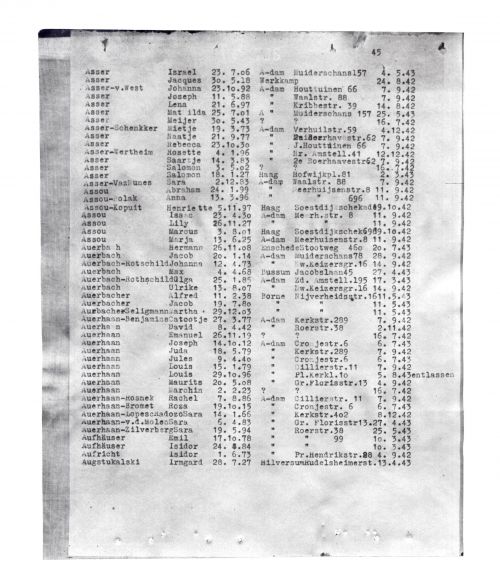

The camp administration consisted of twelve sub-divisions. On August 12, 1943, one of the sub-division heads, Kurt Schlesinger, was appointed chief of the department dealing with the vital main card index, from which the list of deportees was compiled. A Joodsche Ordedienst (OD -Jewish Police), commanded by an Austrian, Arthur Pisk, was also created, with a maximum strength of 200 young men responsible for maintaining order within the camp and seeing off the transports.

Westerbork took on many characteristics of a small town. There was a hospital headed by Dr. Fritz M. Spanier, with 1,800 beds, a maternity ward, laboratories, pharmacies. There were 120 doctors and a further 1,000 employees. Other facilities included an old people's home, a huge modern kitchen, a school for children, aged 6-14, an orphanage and religious services. Workshops existed for stockings repair, tailoring, furniture manufacturing and book binding. There were divisions for locksmiths, decorators, bricklayers, carpenters, veterinarians, opticians and gardeners. The camp also included an electro-technical division, a garage, a boiler room, sewage works and a telephone exchange. During 1943, when the 'permanent' population was at its peak, 6,035 people were employed at the camp, not all of whom were Jewish.

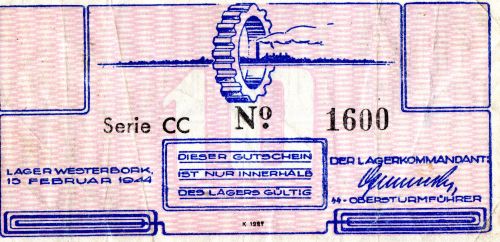

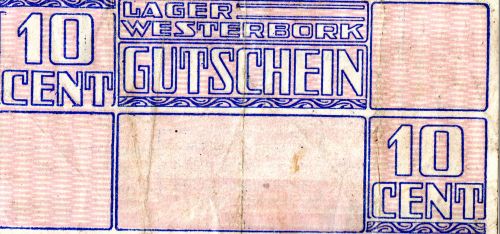

Although men and women were segregated at night, there were no restrictions on their movements during the day. Services within the camp, included dental clinics, hairdressers, photographers, and a postal system. Various sporting activities were available, including boxing, tug-of-war and gymnastics. Albert Gemmeker encouraged entertainment activities - there was a cabaret, a choir and a ballet troupe. Toiletries, toys and plants could be purchased from the camp warehouse. There were no shortages in the camp, since it was regularly supplied by the Dutch administration and Gemmeker had a fund at his disposal appropriated from the Jewish property that had been confiscated. As with some other transit camps, Westerbork had its own currency:

Westerbork Currency (Chris Webb Private Archive)

One should not be fooled into thinking the above represented some idyllic existence, it should be borne in mind that every inmate had the spectre of imminent death hanging over them. The railway line into the camp had been completed in November 1942, and allowed trains into the centre of the camp complex. 101,525 of the 107,000 Jews deported to the east were interned at Westerbork - 41,156 men, 45,867 women, and 14,502 children. More than 95% of those deported from Westerbork perished. The first transport that left Westerbork for Auschwitz arrived there on July 17, 1942, along with a transport from another Dutch transit camp Amersfoort, consisting of 2,000 Jews. From March 2, 1943, the first train from Westerbork to the Sobibor death camp in south-eastern Poland. The last transport from Westerbork to Sobibor left on July 20, 1943. In total nineteen trains went from Westerbork to Sobibor carrying some 34, 313 Jews, the vast majority perished in the second death camp constructed as part of Aktion Reinhardt.

Fear of transport to the unknown East dominated Westerbork and defined the behaviour of many of its inmates. Although no detailed knowledge about the final destination of the transports was known, the inmates were only too aware that the Germans were not planning anything that would prove beneficial to the deportees. In order to keep their names off the transport lists, people would do anything - 'sacrifice their last hoarded halfpenny, their jewels, their clothes, their food or in the case of young girls, their bodies.' Doctor Elie Cohen, described his own role in this process of salvation:

'I had a rather great influence in Westerbork, having become a camp 'prominent,' and I could keep people away from the transports when I choose to do so, for example my own family. As long as I was in power, to put it that way, I was able to protect my parents-in-law, who had arrived in Westerbork in April. I had a cousin in the OD and he warned me on Sunday or Monday, 'Elie, Mum and Dad are on the transport list.' Then I answered, 'Well, let's get them to the hospital.' I had influence on the doctor at the Intake Department, and via that fellow, one was taken in to the hospital, so that their partner was also 'gesperrt.'

As each Tuesday approached, every person incarcerated in Westerbork, had to endure the trauma of possible deportation. These two examples, richly illustrate the horrors of deportation. We start first with the account of inmate Philip Mechanicus, who wrote in his diary:

Tuesday June 1.

The transports are as loathsome as ever. The wagons used were originally intended for carrying horses. The deportees no longer lie on straw, but on the bare floor in the midst of their food supplies and small baggage, and this applies even to the invalids who only last week got a mattress. They are assembled at the hut exits at about seven o'clock by OD men, the Camp Security Police, and are taken to the train in lines of three, to the Boulevard des Miseres in the middle of the camp.

The train is like a long mangy snake, dividing the camp in two and made up of filthy old wagons. The Boulevard is a desolate spot, barred by OD men to keep away interested members of the public. The exiles have a bag of bread which is tied to their shoulder with a tape and dangles over their hips, and a rolled up blanket fastened to the other shoulder with string and hanging down their backs. Shabby emigrants who own nothing more than what they have on and what is hanging from them. Quiet men with tense faces and women bursting into frequent sobs. Elderly folk, hobbling along, stumbling over the poor road surface under their load and sometimes going through pools of muddy water. Invalids on stretchers carried by OD men.

On the platform the Commandant with his retinue, the 'Green Police,' Dr. Spannier, the Medical Superintendent, in a plain grey civilian suit, bareheaded and very dark, with his retinue, Kurt Schlessinger, the head of the Registration Department, in riding breaches and jackboots, a nasty face and straw coloured hair with a flat cap on it. Alongside the train doctors, holding themselves in readiness in case invalids need assistance.

The deportees approaching the train in batches are surrounded by OD men standing there in readiness to prevent any escapes. They are counted off a list brought from the hut and go straight into the train. Any who dawdle or hesitate are assisted. They are driven into the train, or pushed, or struck, or pummelled, or persuaded with a boot, and kicked on board, both by the 'Green Police,' who are escorting the train and by OD men. Noise and nervous outbursts are not allowed, but they do occur. Short work is made of such behaviour - a few clips suffice.

The OD men base their uncouth behaviour on that of their German colleagues, who are lavish in the use of their fists and inflict quick, hard punishment with their boots. The Jews in the camp refer to them as the Jewish SS. They are hated like the plague and people would gladly flay many of them alive, if they dared.

Men and women, old and young, sick and healthy, together with their children and babies, are all packed together into the same wagon. Healthy men and women are put in amongst others who suffer from complaints associated with old age and are in need of constant care, men and women who have lost control over certain primary physical functions, cripples, the old, the blind, folk with stomach disorders, imbeciles, lunatics. They all go on the bare floor, in amongst the baggage and on it, crammed tightly together. There is a barrel, just one barrel for all these people, in the corner of the wagon, where they can relieve themselves publically. One small barrel not large enough for so many people. With a bag of sand next to it, from which each person can pick up a handful to cover the excrement. In another corner there is a can of water with a tap for those who want to quench their thirst.

When the wagons are full and the prescribed quota of deportees has been delivered, they are closed up. The Commandant gives the signal for departure - with a wave of his hand. The whistle shrills, usually about eleven o'clock, and the sound goes right through everyone in the camp, to the very core of their being. So the mangy-looking snake crawls away with its full load. Schlesinger and his retinue jump up on the footboard and ride along for a little bit for the sake of convenience, otherwise they would have to walk back. This would wear out their soles. The Commandant saunters contentedly away. Dr. Spannier, his hands behind his back and his head bent forward in worried concentration, walks back to his consulting room.

We are lucky that Jules Schelvis, survived, because he gave an account of the same transport, as it left Westerbork and headed for Sobibor death camp, on June 1, 1943. His account is a detailed description of the conditions and the horrendous journey the Jews were forced to make:

The train, which departed from Westerbork on Tuesday 1 June, consisting of a long line of freight wagons, was carrying 3,006 persons. There were sixty-two in my wagon, including my wife and her family, plus one pram. The journey took place under the most primitive conditions, lacking even basic provisions such as straw to lie upon , or hooks to hang things from. Apart from two barrels, one filled with water the other for our waste, the men from the Westerbork Orde Dienst (OD -Order Service) had carried aboard a few bread parcels. The sick were wheeled towards the wagons on trolleys. And all of this ostensibly to send us to police-supervised labour camps in Germany, which is how it was put on all the relevant forms. The commandant and his helpers stood by, watching the operations progress.

I have no recollection of any officials in their well-polished shiny boots, concerning themselves with us at all. We had been entrusted to the care of the Jewish Council. Once everyone had clambered abroad, the sliding doors were barred on the outside. With all our luggage, we were packed like a tin of sardines, wondering how long we could endure this. There was hardly any room to stretch one's legs, and only one small barred window, which was unglazed to let some fresh air in.

We left around half-past ten. Only then did we begin to realize that the journey was going to end in some mysterious place. Perhaps Auschwitz; we had heard about Auschwitz. What was certain, however, was that our stamina was going to be severely tested. The train stopped countless times en route in order to let regular and military transports pass. Sometimes we stopped for hours on end for no discernible reason. Throughout the entire journey, the doors were never opened once. We had to relieve ourselves in the little barrel, which soon caused a foul and unbearable stench. Having depleted the water from our own water bottles by the very first evening, we were parched with thirst.

The journey lasted for three long, agonizing days, filled with despair and bickering. We went right across Germany, via Bremen, Wittenberge, Berlin, Breslau and into Poland. In the morning of Friday 4 June, we finally stopped at Chelm, close to what had once been the Russian border. The journey had made us so weary that we were no longer interested in where we would end up. Only one question remained: how to get out of this foul-smelling overloaded cattle wagon, and get some fresh air into our lungs. That Friday morning at around ten, after a seventy-two hour journey, we finally stopped in the vicinity of a camp. It turned out to be Sobibor.

Extract of a Deportation List from Westerbork - 25 May 1943

On February 8, 1944, a transport of 1,015 Jews was deported from Westerbork to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Among them were 268 of the camp's hospital patients, including children with scarlet fever and diphtheria. Many of the sick were brought to the train on stretchers. On arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau, on February 10, 142 men and 73 women were admitted to the camp. The remaining 800 deportees, including all of the 221 children, were gassed. Philip Mechanicus wrote: 'Of all these bestial transports, perhaps this was the most fiendish. '

The last transport from Westerbork to Auschwitz-Birkenau left Holland on September 3, 1944, carrying 1,019 Jews. The transport arrived on September 5, and among the deportees were the Frank family. Anne Frank, the young author of a diary, her father Otto, her mother Edith and her sister Margot. Only the father Otto lives to see the liberation. Anne and Margot perished in the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp and Edith lost her life in Auschwitz.

On the same day the last transport reaches Auschwitz, the camp was crowded with members of the NSB - the Dutch Nazi Party, who tried to flee to Germany after false rumours of an invasion of the country by Allied forces, which became known as 'Mad Tuesday.' The ninety-third and last transport from Westerbork to Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp left on September 15, 1944. After this deportation, less than 1,000 inmates remained in Westerbork.

On April 12, 1945, as Allied forces approached Westerbork, Gemmeker handed the camp over to Kurt Schlesinger. On that day there were 876 prisoners still in the camp, of whom 569 were Dutch. The remainder were of various nationalities or stateless, the majority of them still members of the 'Alte Kamp -Insassen.' Schlesinger proclaimed the camp re-named ' Austausch- Internierungslager' and put it under the protection of the International Red Cross. He handed control of the camp to Mr. Van As, of the Community of Westerbork, a member of the the Dutch civilian authorities.

Albert Gemmeker remained an enigmatic figure. He rarely raised his voice or dealt out punishments to the prisoners, and was said to be incorruptible. He took an interest in the camp's entertainments and afterwards joked with the performers. Jewish gardeners cultivated flowers for him and he was treated by Jewish doctors and dentists. Yet on Tuesdays he stood quietly watching the trains depart for the east. Gemmeker even had a film made in Westerbork which was to show everything good and bad, documenting the camp's daily life. Scenes from the film appear frequently in Shoah-related documentaries. One particularly haunting image from the film, is that of a nine year-old girl staring from the doorway of a cattle wagon, has become synonymous with the Holocaust. The girl, however, was not in fact Jewish, but of Roma descent and she was Settela Steinbach. She perished in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Albert Gemmeker was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment by a post-war Dutch court. Extenuating circumstances were taken into account, in arriving at that sentence, in so much that in general he had treated the Jews decently during their stay in the camp.

After the end of the Second World War Camp Westerbork was used for the internment of members of the Dutch National Socialist Party, the NSB. Not all Jews had left the camp by then. Later, repatriates from Nederlandisch-Indie - now Indonesia were housed in the barracks, especially people from the South -Moluccas.

In 1971, the last barracks were destroyed and on the spot where Camp Westerbork had been, a monument was erected. It was only in 1983, that the Camp Memorial Museum was opened and parts of the former camp area were reconstructed.

Sources

www.holocaustresearchproject.org online resource

Dr. Elie A Cohen, De 19 treinen naar Sobibor, Elsevier, Amsterdam / Brussels 1979

French L. Maclean, The Camp Men, Schiffer Publishing Ltd 1991

Deborah Slier and Ian Shine, Hidden Letters, Star Bright Books Inc New York 2008

Danuta Czech, Auschwitz Chronicle, Henry Holt New York 1997

Jules Schelvis, Sobibor, Berg, Oxford, New York 2007

Transport List - Camp Westerbork Memorial Museum

Envelope and Currency - Chris Webb Private Archive

Photograph - USHMM

Dedicated to Lilli

© Holocaust Historical Society 2018