Bochnia

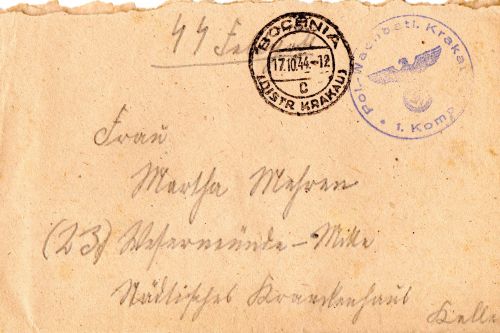

Bochnia Polizei - Wachbat 1 Kompanie -Envelope 1944 (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Bochnia is located 28 miles east –south east of Krakow and in 1939, there was approximately 3,500 Jews living there, comprising approximately 20 percent of the town's population. German forces occupied Bochnia on 3 September 1939, and straight away they began to kidnap Jews for forced labour. Deportations to labour camps began in 1940 and continued through most of the ghetto's existence and sometimes the Jewish community had to pay the transportation costs to the camps. In the autumn of 1939, a Jewish Council (Judenrat) was established in Bochnia to act as an intermediary between the Jewish community and the German authorities. In 1940, Symcha Weiss was appointed as chairman of the Judenrat and a Jewish Police (Judischer Ordnungsdienst) was created under Dr. Szymon Rosen.

The Jewish population grew through the arrival of successive waves of Jewish refugees from Krakow during May 1940, Krzeszowice in March 1941, and Mielec during the spring of 1942. The German authorities established a ghetto in the centre of Bochnia in March or April 1942. Initially the ghetto remained unfenced. The area of the ghetto was about 600 meters by 200 meters, based around Kowalska Street. From July 1941, Jews were not permitted to leave the ghetto without a special permit; by October 1941, the punishment for disobeying this order was death. Over the following 10 months, over 300 Jews were shot in the Jewish cemetery for disobeying this order.

Following the arrival of the Krzeszowice Jews, the ghetto was expanded in April 1941, and included the following streets; Proszowska, Wygoda, Podedworze, Dolne, and the remainder of Krzeczowska Street. Due to the large number of refugees and the very confined space, the ghetto became severely overcrowded, and sanitary conditions were deplorable. The Germans controlled the supply of food into the ghetto and enforced strict rationing. Those who worked received rations that were barely sufficient. To feed the sick and the old, their names were added to the list of productive workers, but their relatives then had to cover for them by working even longer hours to meet high production quotas.

By the end of 1941, about 2,000 Jews were employed in workshops in the ghetto. They manufactured army uniforms, handkerchiefs, underwear, shoes, brushes, toys, electrical equipment, and baskets for the Germans. A German named Wettermann was in charge of these workshops, but a Jew named Salomon Greiwer, oversaw the day-to-day operations. Jews exited the ghetto under escort daily to perform forced labour. To maintain a semblance of their former lives, an elementary school and a Bet Midrash operated within the ghetto until August 1942. There was also a hospital from the end of 1941, which the Germans established to deal with a typhus epidemic. Dr Anatol Gutfreund was in charge. The hospital received some medical supplies, with aid initially received from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC) in Krakow. Nazi restrictions did not extend to Jews who were citizens of some foreign countries, and these Jews were able to provide some contact between the ghetto's residents and the outside world. They also helped to smuggle foodstuffs into the ghetto, gave refuge to children during the deportation 'Aktions' and helped to organise escape routes to Hungary and Slovakia.

In the spring of 1942, the ghetto was enclosed by a wooden fence about 7 feet high, which the Polish (Blue) Police guarded. Mass expulsions throughout the region spread fear among the Jews in the spring and summer 1942. There were reports about whole communities being liquidated. Greiwer tried to reassure the workers that they would remain protected, but many ghetto residents constructed bunkers to hide when the manhunts began. A few days before the first mass deportation in August 1942, the Judenrat was forced to pay the Germans a sum of 250,000 zloty – the latest in a series of demands – supposedly as protection money to guarantee the Jews' safety. However, this proved to be false, and was simply a means to extort money from the Jewish community. All the Jews in the Kreis were gathered together on the evening of Friday 21 August 1942, and were brought to Bochnia the next morning. The entire Jewish community of Nowy Wisnicz, some 1,500 people was transferred to the Bochnia ghetto, along with Jews from a number of villages, including Brzeznica, Bogucice, Lipnica Murowana, Rzezawa, Targowisko, Uscie Solne, and Zabierzow. This relocation caused fear and panic in the Bochnia ghetto, as they now expected a large-scale 'Aktion' – which indeed duly followed, some Jews went into hiding, on their own or with their German employers.

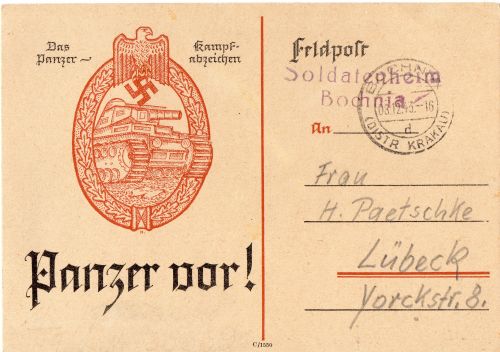

Bochnia Soldatenheim Envelope (Chris Webb Private Archive)

Between 25 -27 August 1942, the Gestapo, SS troops, and their Ukrainian –SS auxiliaries surrounded the ghetto. Then assisted by the Jewish Police, rounded up the Jews and selections were conducted. As so many people were in hiding, there was a shortage of deportees, even people holding special permits were included in the deportation, and Jewish policemen had to bring their own family members. Those who were unwilling or unable to follow orders were shot in front of their families. Among those murdered was Salomon Greiwer, who tried to save his workers. The Gestapo shot a number of Jews within the ghetto and a group of approximately 800 elderly and sick Jews, including some from the hospital were loaded onto trucks with the assistance of Baudienst members and transported to the village of Baczkow, where they were thrown into a pit and shot, though some were buried whilst still alive. The remaining Jews on the market-square comprising of healthy and strong Jews, were loaded onto a waiting train and sent to the Belzec death camp, where they were murdered in the gas chambers. Almost the entire complement of the Judenrat went on the last transport to Belzec death camp. They went along to reassure the deportees that the Nazis really were resettling them in the east. In total, more than 5,000 Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp during the August deportations.

After the 'Aktion' the remaining ghetto residents again had to pay for their right to survive, which they ironically called 'slaughter money.' Officially there were still approximately 1,000 Jews left in the ghetto, plus an additional 400, so-called 'illegal's' in hiding. The number soon increased to around 5,000 again, however, as many Jews emerged from hiding in Bochnia, and the surrounding countryside. The head of the Gestapo in Bochnia, SS- Untersturmführer Wilhelm Schomberg, issued the Jews special permits allowing them to remain, and the workshops resumed production, now employing some 3,000 people. During a second 'Aktion' on 10 November 1942, 150 were shot, whilst around 570 were sent to Belzec death camp. That same day, the Germans announced that Bochnia would be one of the five remaining towns in the Krakow District where Jews could live in a Jewish residential area (Judenwohnbezirk). As a result, the ghetto population again swelled to more than 5,000, as Jews emerged from hiding and settled in the ghetto.

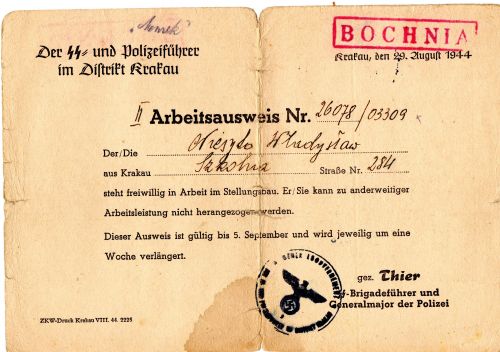

Bochnia - Arbeitausweis signed by Thier (Holocaust Historical Society)

In Ghetto 'B' this contained those who did not work, including the children, the elderly, the sick and disabled. The new private owners were obliged to pay the SS for the right to exploit Jewish forced workers. The Bochnia Jewish community had officially ceased to exist, and children had to be hidden, as they were forbidden in the labour camp.

The Hebrew youth movement Akiba was active in Bochnia before the war, and from 1940 onwards its members established an Underground cell in the town, which co-operated with a branch of Zydowska Organizacja Bojowe, Jewish Fighting Organisation, ZOB) in Krakow. The Bochnia Underground dealt in providing false identification papers and preparing bunkers in the forest, as a base for resistance operations. ZOB members were recruited in the ghetto, and after December 1942 the Underground members were located in Ghetto 'B.' From this base they maintained communications with sections of the Polish Underground and also with ZOB members in Krakow. On Friday 26 February 1943, the Germans arrested most of the Underground members in Bochnia. Surviving ZOB leaders fled to the forest to continue the armed struggle against the Nazis. They remained in contact with the remaining cell inside the ghetto, until the ghetto was finally liquidated.

In the early spring of 1943, another 'Aktion' took place in which 100 Jews were sent to the Plaszow Forced Labour Camp in Krakow. A few months later in July 1943, there was a scramble in the ghetto to purchase false documents showing foreign citizenship, as it was rumored that any foreign Jew who paid a large sum, would be able to migrate to the United States of America. However, the ruse was soon exposed when approximately 100 Jews were not sent to the United States of America, but went to Plaszow, where the Germans shot all but two of them.

The final liquidation of the Bochnia ghetto started on 1 September 1943, when at 5.00 a.m. the SS forces surrounded the ghetto, and roused the residents from their beds, with orders to go to the 'Appellplatz.' Once there, they were divided into two groups: One contained most of the inhabitants of Ghetto 'B,' including all of the children and the elderly. This group, numbering approximately 3,000 people was sent to Auschwitz concentration camp to be murdered, or selected for slave labour. This transport arrived at Auschwitz on 2 September 1943, and 830 were selected for slave labour, whilst 2,170 people were gassed. The other group, comprising of approximately 1,000 people, aged between 13-35, was transported to the Szebnie camp on 3 September 1943, where most of them died.At the communal cemetery in Bochnia, some 60 people were shot and their bodies burned. Officially, only 150 Jews were allowed to remain in Bochnia as a work detail to clear the ghetto, along with a few members of the Jewish Police. Another 100 people joined the work detail. However, when this was discovered the next day, 100 people were shot at random in the streets. Those remaining were forced to pile up the dead and burn the bodies. These 150 people worked until December 1943, and then 100 were sent to Szebnie and 50 were sent to Plaszow.

Many Jews hid during the last 'Aktion,' but most were discovered over the following six weeks. The Jews in the work details tried to help them, but the Germans used dogs and smoke to force the Jews out of their hideouts, and once caught murdered them. Most who tried to escape were murdered either by Germans or Polish extremists, although a few Jews managed to escape to Hungary. The total death toll for the Bochnia ghetto was at least 13,000 Jews deported to death camps at Belzec and Auschwitz, whilst over 1,800 Jews were killed in Bochnia and its vicinity.

Sources:

The Encyclopaedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933-1945, USHMM, Indianna University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis 2012

Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka – The Aktion Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987

R.O'Neil, Belzec, Stepping Stone to Genocide, JewishGen Inc, New York 2008

D. Czech, Auschwitz Chronicle, Henry Holt & Co, New York 1989

Envelopes - Chris Webb Private Archive

Document - Holocaust Historical Society

© Holocaust Historical Society September 14, 2024