The Sobibor Area Labour Camps

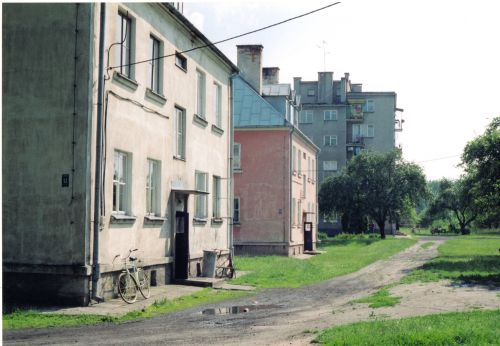

Adampol - July 2004 (Chris Webb Private Archive)

In accordance with the German plans at the very beginning of the occupation, the Lublin district was intended to become 'the pillar of the GeneralGouvernement's agricultural policy.In order to modernise the agriculture in this region, the German authorities wanted to regulate the small rivers and to improve the meadows. Therefore the Wasserwirtschaftsinspektion (Inspection for the Water Economy) in the Lublin district installed a network of small work camps during 1940. Jewish and Polish prisoners worked there. Chelm County became one of several centres for these camps. The Sobibor death camp was built in this district in early 1942.

In 1940, Jews mainly from the Lublin and Warsaw districts were sent to these work camps. They received an official salary of 96 zloty per month, but this amount was poor reward for the extremely hard work in often very difficult conditions. These forced labour camps were set up in the swampy surroundings of Sobibor. They were located at Adampol, Czerniejow, Dorohusk, Kamien, Krychow, Luta, Nowosiolki, Osowa, Ruda Opalin, Sawin, Siedliszcze, Sobibor village, Staw-Sajczyce, Tomaszowka, Ujazdow, Wlodawa, and Zmudz.

In some places the camps were located in school buildings, abandoned farms, or industrial buildings. Except for the camp at Krychow, the prisoners lived in barns on private farms or in a mill, in the case of Staw-Sajczyce. The camps were under the supervision of the German civil administration but the prisoners were guarded by Trawniki-manner or by the Jewish Police in Osowa. In the camp at Sawin, the Jewish prisoners were also supervised by Jewish Police and Polish Guardsmen, who worked for the Wasserwirtschaftsinspektion.

The prisoners were forced to work 8 -10 hours daily, most of the time they stood in water in wet clothes, without the opportunity to change them. Food was also a major problem. Only those who came from towns close to the camps had the opportunity of obtaining some food from home. The Jews taken from the Warsaw Ghetto or Warsaw district depended on the camp's kitchens. If they had some money they could buy bread from the local peasants. In some camps like Krychow, the prisoners were killed when camp commandant Adolf Loeffler discovered they had made contacts with local Poles. The Polish farmers accused of selling food to the prisoners were beaten. In Osowa these contacts were not so strictly forbidden. Because they had no money the Jews exchanged their clothes for food.

In 1941, alone, 2,500 out of 8,700 Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto had to be released from the camps because of sickness. Many Jews died of starvation, typhus epidemics and the harsh working conditions. In several camps such as Osowa or Sawin they were shot in mass executions. In the autumn of 1941, in Osowa, the last remaining group of 58 Jewish prisoners were executed close to the camp. Two of them survived and became functionaries in the next period between 1942, and 1943.

In 1941, approximately 2,200 Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto were sent to Krychow, Osowa, Sawin, and Staw-Sajczyce. The number of people who were released from these camps during June and July 1941, when almost all the large buildings were taken over by the German Wehrmacht at the beginning of the war against the Soviet Union, is not known. In Osowa the average number of prisoners was 400 -500 people, in Siedliszcze,approximately 2,000 and in Sawin 700 -800.

Krychow was the largest camp within the network, located south-west of Sobibor close to Hansk village. It was built before the Second World War as a detention camp for Polish criminals. Even then the prisoners had to regulate the rivers of this region. In 1940, the Hansk local administration received an order from the German civil administration to prepare buildings of the former camp for transports of Gypsies. These were Gypsies from the Gypsy camp in Belzec. The whole group of Gypsies have been estimated to have been between 1,000 and 1,500 people. According to the statements by Polish witnesses from Hansk, the Gypsies in Krychow were not guarded and not forced to work. Most of them could not speak Polish. They exchanged their clothes for food and begged for money. In the autumn of 1940, they were deported from Krychow. Some of them were sent to the Siedlce Ghetto.

Between the end of 1940, and early 1941, most of the prisoners in Krychow were Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto and local Polish and Ukrainian farmers, arrested for not having paid their impositions. Around 1,500 prisoners in Krychow, according to witnesses in Hansk, were beaten by the guards and suffered from starvation and illness. 150 Jews worked as manual workers. Many Jews had to work in fields that belonged to the German 'Colonists,' or at the manors taken over by the Germans. Even women and children between eight and twelve years old, had to work there. With the beginning of Aktion Reinhardt all of these forced labour camps were reserved for Jews only. After their families had paid sums of money for their release, they were set free at the beginning of 1942.

Krychow - Former villa of the Camp Kommandant (Arttur Hojan)

The Jews arrived from the liquidated ghettos in the surroundings of Sobibor, Rejowiec, Siedliszcze, Sawin, Wlodawa and Chelm or were sent after selection to the Sobibor death camp; the transports from abroad were subjected to selections. People from Slovakia, Holland, Germany and Austria did not realise or could not believe that their relatives and friends were being led away to be murdered in the gas chambers. Sobibor was almost unique in selecting large groups of prisoners to work in other camps. It is unknown how many people were selected at Sobibor for work in the local forced Labour Camps.

Franz Stangl, the commandant of Sobibor, recalled in an interview with Gitta Sereny, his visit to the Krychow Labour Camp during April 1942:

Baurat Moser suggested we make a round of the camps he supplied in the district. The first camp I saw was about half-way between Chelm and Sobibor, a farm called Krychow, It employed two to three hundred Jewish women, mostly German or at least German speaking. I went in there to look around. There was nothing - you know - sinister about it: they were quite free, if you like:it was just a farm where the women worked under the supervision of Jewish Guards. Well I suppose you could call them Jewish Police. As I say I looked around and the women seemed quite cheerful - they seemed healthy. They were just working, you know. They were armed with weissen Schlagmitteln (white implements for beating).

Aside from the difficult conditions of life and work, in spring and summer, mosquitoes were a big problem and selections in the camps were regularly organised. Sick people and children were sent by horse-drawn carts or by foot to the Sobibor death camp. In the camps located very close to Sobibor, the inmates knew about the death camp. This psychological pressure shattered their will to resist and survive. In many Polish testimonies, the witnesses mentioned the passivity of the prisoners. In Osowa village, 7 kilometers away from Sobibor and surrounded by a vast forest, no prisoners escaped from the camp, although some Poles attempted to help them.

SS-Arbeitslager Dorohucza, which was located half-way between Lublin and Chelm, some five kilometers from Trawniki became operational in late February and early March 1943. Here prisoners were forced to dig peat, in very harsh conditions. Out of the 500 Jews, about half of them were Dutch Jews selected on the ramp at the Sobibor death camp.

The Commandant of Dorohucza was SS-Hauptscharfuhrer Gottfried Schwarz, who had served with distinction at the Belzec death camp. According to other SS Officers, Robert Juhrs and Ernst Zierke, who also served at Belzec and Sobibor death camps, it was confirmed that the last commandant of Dorohucza was Fritz Tauscher, who had also served at the Belzec death camp.

Dorohucza camp was liquidated during the Aktion Erntefest massacre in November 1943, when the Jewish prisoners in most of the Jewish Labour Camps in the Lublin district were brutally murdered in early November 1943. Robert Juhrs recalled the events of November 1943:

After the Jews had vacated their barracks, their quarters were searched. Then the Jews guarded by the police unit left in the direction of Trawniki. I found out later that all the Jews from this commando were shot near the trenches within the Trawniki command area. A few days after the operation, we received orders from Lublin to go to Sobibor.

Only during the final liquidation of the Adampol Labour Camp near Wlodawa on August 13, 1943, did some of the prisoners who were in contact with the partisans, try to organise any resistance and fight against the police. It is important to mention that most of the inmates in Adampol were Polish Jews who knew their fate. During the liquidation of this camp, 475 Jewish prisoners were executed on the spot. Most of the foreign Jews had no possibility of escaping because they did not know the language, the region, or the people.

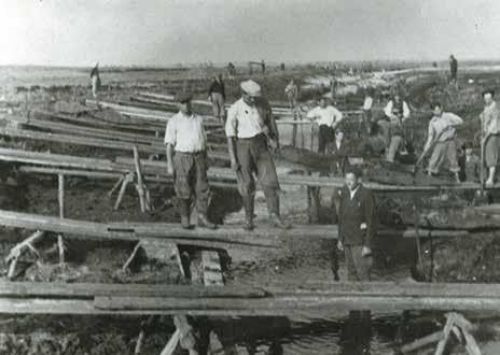

Sawin Labour Camp (Sobibor Museum Wlodawa)

In Sawin, successful escapes by two Czech Jews are known, one of those who escaped lost his mother during a selection in Sawin, and only found out after the war that Sawin was not far away from the Sobibor death camp. In other camps the biggest group of prisoners were Jews from outside of Poland. Polish witnesses very often mention their frequent close contact with Czech Jews. Polish farmers realised that among the deportees were Jews who had converted to Christianity. For example, in Sawin, a dentist from Czechoslovakia was a member of the church choir, and her son played the violin during mass. Christian Jews from Czechoslovakia were also in Krychow.

Zygmunt Leszczynski from Hansk stated:

Among the Jews who were in the camp in Krychow there were also Catholics. I saw how, during the transport to Krychow some of them stopped before the cross which was close to the street and they crossed themselves and prayed. I saw also that some of them wore small crosses on the chest.

In the summer and autumn of 1943, most of these Labour Camps were liquidated and their inmates were sent to the Sobibor death camp. From Krychow the prisoners were taken on horse-drawn wagons. From Sawin they had to walk and many of them were killed on the way to the death camp.

Henryk Stankiewicz from Sawin made a statement:

I remember we were together with my father in front of our house 5 -8 meters away from the street. Suddenly we saw the 'Kalmuk' - probably a Ukrainian guard - and behind him several hundred marching people in a column. They walked very slowly and looked starved and dirty. Several of them took off their hats and told us words of farewell: 'Goodbye Mr Stankiewicz we are going to the fire.'

After the selections in the Labour Camps and during their final liquidations the Germans forced the Polish farmers to use their horse-drawn wagons to transport the old people and the invalids. In front of the main gate of the death camp in Sobibor, the Poles had to abandon the wagons and Ukrainian guards from the camp drove the wagons through the gate. Then the Poles heard the victims screaming and after one or two hours the wagons were brought back to them.

Probably the last camp to be liquidated was in Luta village. The camp existed, according to the testimonies of local inhabitants, until the Sobibor revolt on October 14, 1943. The inmates from Luta observed a group of Sobibor death camp prisoners who tried to escape to the nearby forest. After the revolt the Jews from Luta were taken to the death camp and murdered.

In Osowa, a small cemetery can be seen with graves of the prisoners who died in the camp. It is very difficult to say how many people passed through the Sobibor area work camps, or perished there.

Sources

Chris Webb, The Sobibor Death Camp, ibidem-verlag, Stuttgart 2017

Gitta Sereny, Into That Darkness, Pimlico, London, 1974

Jules Schelvis, Sobibor, Berg, Oxford, New York 2007

Thanks to Robert Kuwalek and Lukasz Kukawski (Sobibor Museum Wlodawa)

Photographs: Chris Webb Private Archive, Artur Hojan and Sobibor Museum Wlodawa

© Holocaust Historical Society December 3 , 2021